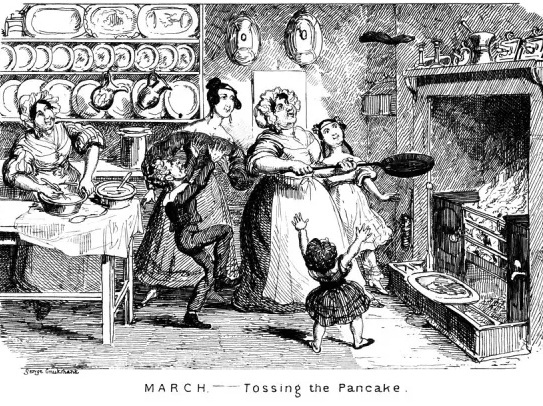

There is something wonderful about food. Why else would we watch shows about cooking, buy cook books, and even enjoy reading (and writing) about food. Regency England was also an era that enjoyed its food.

There is something wonderful about food. Why else would we watch shows about cooking, buy cook books, and even enjoy reading (and writing) about food. Regency England was also an era that enjoyed its food.

There was interest enough in food skills that by 1765 Hanna Glasse’s The Art of Cookery, Made Plain and Easy had gone into nine editions, selling for five shillings if bound. (Back then, one could buy unbound books and have them custom bound to match the rest of the books in one’s library.) Hanna’s book remained popular for over a hundred years. However, her recipes can be difficult to translate into modern terms–the quantities often seem aimed to feed an army, as in this recipe for ‘An Oxford Pudding’:

“A quarter of a pound of biscuit grated, a quarter of a pound of currants clean washed and picked, a quarter of a pound of suet shred small, half a large spoonful of powder-sugar, a very little salt, and some grated nutmeg; mix all well together, then take two yolks of eggs, and make it up in balls as big as a turkey’s egg. Fry them in fresh butter of a fine light brown; for sauce have melted butter and sugar, with a little sack or white wine. You must mind to keep the pan shaking about, that they may be all of a light brown.”

I’ve yet to try this recipe, and when I do I’ll probably substitute vegetable oil for suet, but it does sound tasty.

Amounts in older cookbooks are also often confusing to the modern reader, often listing ingredients to be added as handfuls, as in the rue, sage, mint, rosemary, wormwood and lavender for a “recipt against the plague” given by Hanna Glasse in The Art of Cookery made Plain and Easy.

The time spent on making these recipes could also be considerable. This was an era when labor was cheap, and if one could afford servants, they could provide that labor. The Prince Regent’s kitchen in Brighton was fit for a king of a chef, and large enough to allow an army of cooks, pastry chefs, under cooks, and scullery maids. It also sported windows for natural light as well as large lamps, and pillars in the shape of palm trees to carry on the exotic decor of the rest of the Brighton Pavilion. Elaborate dishes could be concocted both for the well and the sick.

The time spent on making these recipes could also be considerable. This was an era when labor was cheap, and if one could afford servants, they could provide that labor. The Prince Regent’s kitchen in Brighton was fit for a king of a chef, and large enough to allow an army of cooks, pastry chefs, under cooks, and scullery maids. It also sported windows for natural light as well as large lamps, and pillars in the shape of palm trees to carry on the exotic decor of the rest of the Brighton Pavilion. Elaborate dishes could be concocted both for the well and the sick.

Shank Jelly for an invalid requires lamb to be left salted for four hours, brushed with herbs, and simmered for five hours. There are few today who have time for such a recipe, unless they, too, are dedicated cooks.

Sick cookery is an item of importance as well for this era. Most households looked after their own, creating recipes for heart burn or making “Dr. Ratcliff’s restorative Pork Jelly.” Coffee milk is recommended for invalids as is asses’ milk, milk porridge, saloop (water, wine, lemon-peel and sugar), chocolate, barley water, and baked soup. (Interestingly, my grandmother swore by an old family recipe of hot water, whisky, lemon and sugar as a cough syrup, and that’s one recipe I still use.)

As interest expanded, and a market was created by the rise of the middle class, other books came out. Elizabeth Raffald had a bestseller with The Experienced English Housekeeper. The first edition came out in 1769, with thirteen subsequent authorized edition and twenty-three unauthorized versions.

In 1808, Maria Rundell,

In 1808, Maria Rundell, wife of the famous jeweler (and a correction is needed here–I started reading how there was confusing about her being wife of the jeweler or a surgeon. It seems she married Thomas Rundell, brother of Philip Rundell, who was the jeweler. So she was the sister-in-law, not wife, but she did some out with her book, published by John Murray) came out with her book A New System of Domestic Cookery for Private Families. This book expanded on recipes to also offer full menu suggestions, as well as recipes for the care of the sick, household hints, and directions for servants. This shows how the influence of the industrial revolution had created a new class of gentry, who needed instructions on running a household, instructions that previously had been handed down through the generations with an oral tradition. The rise of the “mushrooms” and the “cit”, merchants who’d made fortunes from new inventions and industry, created a need for their wives and daughters to learn how to deal with staff and households.

Any good wife had much to supervise within a household, even if the servants performed much of the actual work.

A household would make its own bread, wafers, and biscuits, brew its own ale, distill spirits, and make cheese. In the city, some of these would be available for purchase. Fortnum and Masons specialized in starting to produce such ‘luxury’ goods (jams and biscuits, or what we Americans would call cookies).

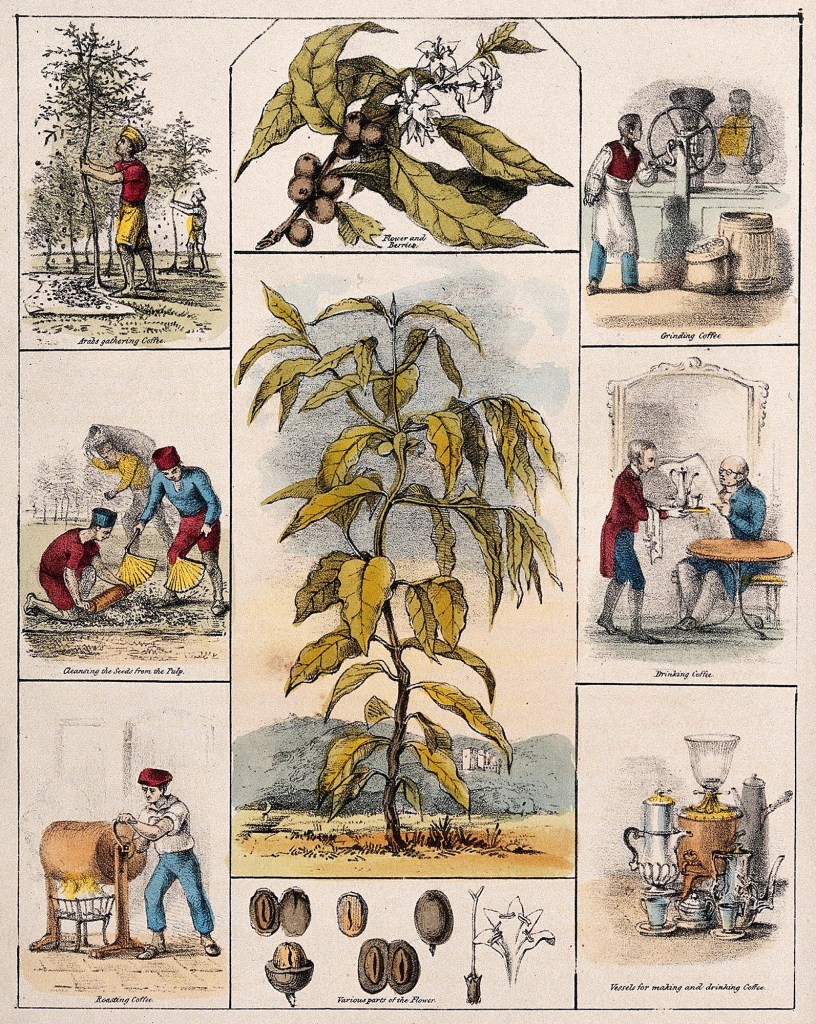

In London, wines would be purchased from such places as Berry Brothers, a business still in existence as Berry Bros & Rudd. Establish in the late 1600’s at No. 3 St. James’s St., the store initially supplied coffee houses with coffee and supplies. They expanded into wines when John Berry came into the business due to marriages and inheritance. Berrys went on to serve individuals and London clubs such as Boodles and Whites with coffee, wines, and other goods. They put up their ‘sign of the coffee mill’ in the mid 1700’s, and Brummell as well as others used their giant coffee scale to keep an eye on his weight and keep his fashionable figure.

Laura Wallace offers more information on wines and spirits of the Regency (http://laura.chinet.com/html/recipes.html. She notes Regency wines: port, the very popular Madeira, sherry, orgeat, ratafia, and Negus, a mulled wine. Other wines you might find on a Regency dinner table include: burgundy, hock (pretty much any white wine), claret, and champagne (smuggled in from France).

For stronger spirits, Brandy was smuggled in from France. Whiskey, cider, and gin were also drunk, but were considered more fitting for the lower class. (Whiskey would acquire a better cachet in the mid to late 1800’s, due to the establishment of large distilleries and after it again became legal. The Act of Union between Scotland and England in the early 1700’s and taxation drove distillers into illegal operation. After much bloodshed, and much smuggling, the Excise Act of 1823 set a license fee that allowed the distillery business to boom.)

For weaker fare, ale, porter, and beer were to be found in almost any tavern, and would be brewed by any great house for the gentlemen. Water as a beverage, was often viewed with deep suspicion, wisely so in this era, but lemonade was served.

As Laura Wallace notes on her site, “port, Madeira and sherry are heavy, ‘fortified’ wines, that is to say, bolstered with brandy (or some other heavy liquor). Port derives its name from the port city of Oporto in Portugal. Madeira is named for an island of Portugal…

“Madeira is particularly noted as a dessert wine, but is often used as an aperitif or after dinner drink, while port is only for after dinner, and historically only for men. ‘Orgeat’ is… ‘a sweet flavoring syrup of orange and almond used in cocktails and food.’ Ratafia is…a sweet cordial flavored with fruit kernels or almonds.”

In the country, a household functioned as a self-sufficient entity, buying nothing other than the milled flour from the miller (although many great houses might also grown their own wheat and mill it), and perhaps a few luxuries that could not be produced in England, such as sugar, tea, coffee, chocolate, and wines that could not be locally produced. Fish could be caught locally; sheep, beef, and pigs were raised for meat as well as hides and fat for tallow candles; chickens, ducks, and other tame birds were raised for eggs and for their feathers (useful things in pillows); wild birds, deer and other game could be hunted on great estates; bees were raised for honey and wax candles of a high quality; breweries and dairies were found on every estate, and every house would have its kitchen garden with vegetables and herbs. Berry wines could be made in the still room, along with perfumes, soaps, polishes, candles and other household needs. Many of the great houses also built greenhouses or orangery to produce year round, forcing early fruits, vegetables, and flowers, and providing warmth for the production of exotics such as oranges and pineapples. (The concept of heating with local hot springs had been introduced to England by the Romans, and was still around in Regency Era, and many new innovations were also being introduced for better heating and water flow into homes.)

For a gentlemen who lived in the city without a wife or a housekeeper, cheap food could be purchased from street vendors in London, but most meals would be taken at an inn, a tavern, or if he could afford it, his club. Many accommodations provided a room, and not much more, with the renter using a chamber pot that would be emptied into the London gutters, and getting water from a local public well (and this shared water source accounted several times for the spread of cholera in London). Cheaply let rooms had no access to kitchens. Hence the need for a good local tavern, or to belong to a club.

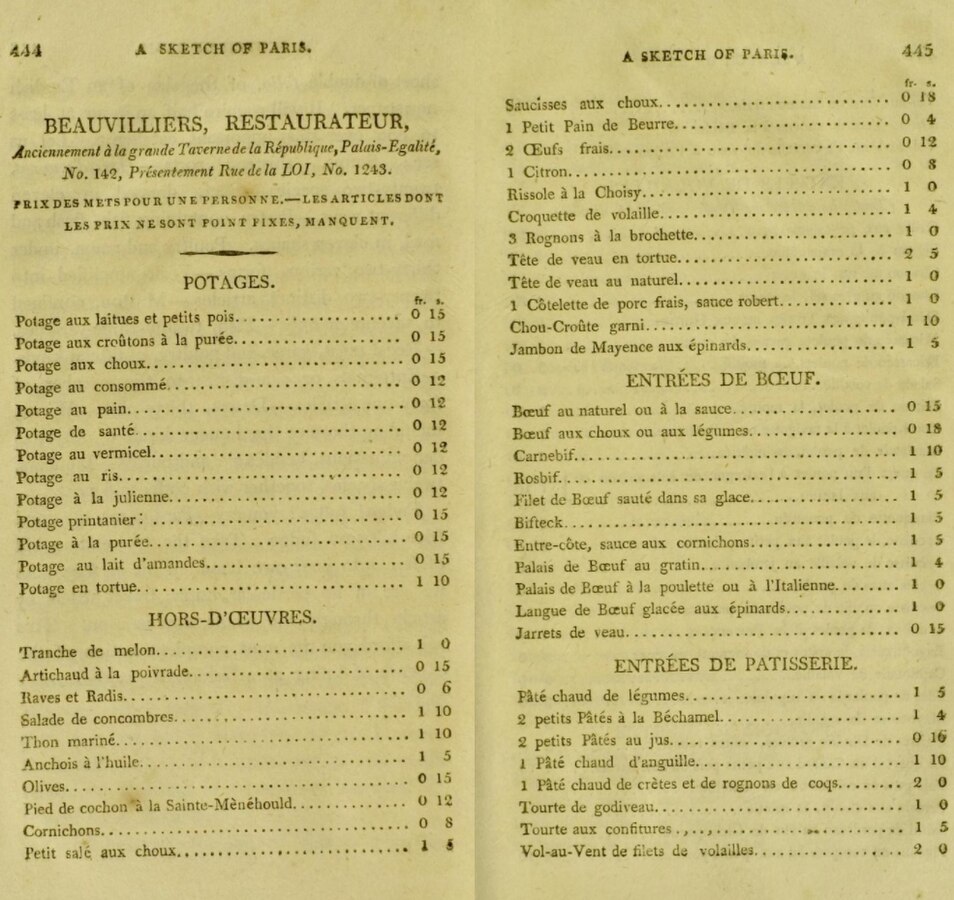

According to Captain Gronow, remembering Sir Thomas Stepney’s remarks, most clubs served the same fare, and this would be, “‘the eternal joints, or beef-steaks, the boiled fowl with oyster sauce, and an apple tart.'” From this remark about the poor quality of food to be had, the Prince Regent is said to have asked his cook, Jean Baptiste Watier to found a dining club where a gentleman could have a decent meal. Headed by Labourie, the cook named by Waiter to run the club, it served very expensive, but excellent meals. It was no wonder that a single gentleman might well prefer to perfect his entertaining discourse so he might be invited to any number of dinners at private houses.

As with all eras, in the Regency, meals provided a social structure for life.

To start the day in London, a fashionable breakfast would be served around ten o’clock, well after most of the working class had risen and started their day. The Regency morning went on through the afternoon, when morning calls were paid. In London, five o’clock was the ‘morning’ hour to parade in Hyde Park. A Regency breakfast party might occur sometime between one and five o’clock in the afternoon.

To start the day in London, a fashionable breakfast would be served around ten o’clock, well after most of the working class had risen and started their day. The Regency morning went on through the afternoon, when morning calls were paid. In London, five o’clock was the ‘morning’ hour to parade in Hyde Park. A Regency breakfast party might occur sometime between one and five o’clock in the afternoon.

During morning calls, light refreshments might be served. Ladies might have a ‘nuncheon’ but the notion of lunch did not exist. Also, the lush high tea now served at most swank London hotels actually originated as a working class dinner, and was perfected by the Edwardians into an art form, but was not a Regency meal.

In London, the fashionable dined between five and eight, before going out for the evening. This left room for a supper to be served as either a supper-tray that might be brought into a country drawing room, or as a buffet that would be served at a ball. Such a supper would be served around eleven but, in London, this supper could be served as late as nearly dawn.

Country hours were different than city hours. In the country, gentlemen would rise early for the hunt or to go shooting. Breakfast would be served after the hunt, with only light refreshments offered before hunting. These hunt breakfasts might be lavish affairs, and if the weather was good, servants might haul out tables, silverware, china, chairs and everything to provide an elegant meal. Again, tea might be taken when visitors arrived in the country, and this would include cakes being served, along with other light sweets.

Dinner then came along in the Regency countryside at the early hour of three or four o’clock. This again left time in the latter evening for a tea to be brought round, with light fare, around ten or eleven. A country ball might also serve a buffet or a meal during the ball, or a dinner beforehand.

From the Georgian era to the Regency the method for serving dinner changed. “…as soon as they walked into the dining-room they saw before them a table already covered with separate dishes of every kind of food…,” states The Jane Austen Cookbook.

The idea was that with all courses laid on the table, those dining would choose which dishes to eat, taking from the dishes nearest. It was polite to offer a dish around. Food in History notes, “It was a custom that was more than troublesome; it also required a degree of self-assertion. The shy or ignorant guest limited not only his own menu but also that of everyone else at the table. Indeed, one young divinity student ruined his future prospects when, invited to dine by an archbishop who was due to examine him in the scriptures, he found before him a dish of ruffs and reeves, wild birds that (although he was too inexperienced to know it) were a rare delicacy. Out of sheer modesty the clerical tyro confined himself exclusively to the dish before him….”

The idea was that with all courses laid on the table, those dining would choose which dishes to eat, taking from the dishes nearest. It was polite to offer a dish around. Food in History notes, “It was a custom that was more than troublesome; it also required a degree of self-assertion. The shy or ignorant guest limited not only his own menu but also that of everyone else at the table. Indeed, one young divinity student ruined his future prospects when, invited to dine by an archbishop who was due to examine him in the scriptures, he found before him a dish of ruffs and reeves, wild birds that (although he was too inexperienced to know it) were a rare delicacy. Out of sheer modesty the clerical tyro confined himself exclusively to the dish before him….”

This style of serving dinner was known as service à la française. During the Regency this was replaced by service à la russe in which the dishes were set on a sideboard and handed around by servants.