I’m get ting the follow up book to Lady Scandal ready to release–Lady Chance (ISBN-978-0-9850265-9-2) will be Book 2 in the Regency Ladies in Distress series–yes, there’s going to be a Book 3 in this series. What’s the book about?

ting the follow up book to Lady Scandal ready to release–Lady Chance (ISBN-978-0-9850265-9-2) will be Book 2 in the Regency Ladies in Distress series–yes, there’s going to be a Book 3 in this series. What’s the book about?

Can an English lady find love and common ground with a French soldier?

In Paris of 1814, as Bourbon king again takes the throne, and the Black Cabinet—a shadowy group of agents employed by the British—is sent to unmask dangerous men and stop assassinations. When Diana, Lady Chauncey—known as Lady Chance—is recruited by her cousin to use her skill at cards to help him delve into these plots, she meets up with a man she thought dead. Diana finds herself swept into adventure and intrigue, and once again into the arms of the French officer who she tangled with ten years ago. But she is no longer an impulsive girl and he may not be the man she once thought was honorable and good.

After the recent defeat of his country, Giles Taliaris wants nothing more than a return to his family’s vineyards in Burgundy. But his younger brother seems involved in dangerous plots to return France to a republic. To get his family through these troubles, Giles can only tread warily. When he again meets meet the English girl he once knew and thought lost to him, he finds himself torn between duty and desire. Can he find his way through this tangle—and if he does, how can he convince his Diana to give up everything for him?

The book took longer than I thought it would to write–there was the research, and interruptions from the idea of building a house–but it has been fun. I do have to thank everyone who kept writing me and bugging me for Diana’s story–you kept me motivated to get it done.

There was a lot of fun–and more research, as always–to write the book. Since it’s set in Paris of 1814, and since gambling and cards are in the book, that meant I could use the Palais Royal, a place I once visited, which was built in the 1600’s.

There was a lot of fun–and more research, as always–to write the book. Since it’s set in Paris of 1814, and since gambling and cards are in the book, that meant I could use the Palais Royal, a place I once visited, which was built in the 1600’s.

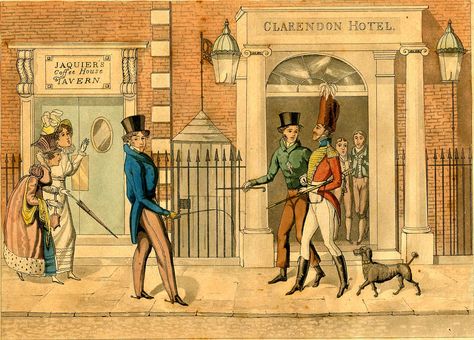

On the ground floor, shops sold “perfume, musical instruments, toys, eyeglasses, candy, gloves, and dozens of other goods. Artists painted portraits, and small stands offered waffles.” The demi-monde could also parade their wares—themselves–and often had rooms on the upper floors for their customers’ convenience. By 1807, the Palais Royal boasted “twenty-four jewelers, twenty shops of luxury furniture, fifteen restaurants, twenty-nine cafes and seventeen billiards parlors.” While the more elegant restaurants were open on the arcade level to those with the money to afford good food and wine, the basement of the Palais Royal offered cafés with cheep drinks, food and entertainment for the masses, such as at the Café des Aveugles.

The Palais des Tuileris also serves as a setting. Sadly, it no longer stands, having been burned in 1871. The Tuileries Garden, or Jardin des Tuileries, still are there, but in 1814, the Palais des Tuileris, with the Salle de Maréchaux, which took up two floors of the central Pavillon de L’Horloge, was a symbol for Louis XVIII’s return to power.

The Palais des Tuileris also serves as a setting. Sadly, it no longer stands, having been burned in 1871. The Tuileries Garden, or Jardin des Tuileries, still are there, but in 1814, the Palais des Tuileris, with the Salle de Maréchaux, which took up two floors of the central Pavillon de L’Horloge, was a symbol for Louis XVIII’s return to power.

Weaving in the textures of Paris, the excitement of a city just coming out of war, the uncertainty of those times was great fun.

If you would like an early copy to read so you can post a review once it goes up on sale, email me at Sd@sd-writer.com. The book should be on sale by August 20! Then it’s time to get a few novellas done before Jules’ story.

READ AN EXCERPT

Closing her eyes, Diana pulled in a deep breath of crisp air. Dawn had come up less than an hour ago and she still had not seen her bed. Jules had taken her to three other gaming salons, including the elegant and excessively luxurious Cercle des Etrangers, in the rue de la Grand Batelière. The play had been quiet and deep in the third, the gentlemen and a few ladies hardly looking up from their cards to acknowledge any arrivals. She had enjoyed a few hands, but she had been distracted by the night and won only a little. Jules took her at last to the small hôtel on the Ile St-Louis he had rented for them.

It was not an English hotel, but a furnished house to let, with servants and lovely rooms left intact from the era before the Revolution had torn France apart. She had stayed only long enough to wave off her yawning maid and change into a serviceable, sage-green walking dress and ankle boots. With a straw bonnet slapped on, she pulled one of Jules’ hulking black umbrellas from the brass stand in the hallway. The porter held the door for her. She wondered if he thought the English were quite mad to be forever dashing about.

She crossed on the nearest bridge and made for the Palais des Tuileries and their gardens, her skirts swirling about her ankles along with the river’s damp. Even though the hour was early, Paris seemed filled with soldiers. Jules had said the Prussians had claimed the Champs-de-Mars, around the Invalides, and the Luxembourg Garden for their camp, and also the Place du Carrousel near the Palais des Tuileries. She could see faint smoke from fires and heard the clatter of tin cups and plates. The British troops camped along the Champs-Elysées, the Dutch in Bois de Boulogne, and the Russians—well, she had no wish to meet up with Cossacks for she disliked their monstrous whiskers that made them look more like bears than men.

The gardens that fronted the Palais des Tuileries offered trees just starting to bloom and trim paths that had long been open to everyone. The trees stood bare still with only a promise of leaves curled tight in pale, green buds.

It was unlike England’s parks. Far more tame, the trees and shrubbery seemed pretty and light and were nothing Diana could name. She had never been much of a gardener. Jules had promised a visit to Chateau Malmaison to see Madam Josephine’s famous roses, but Diana had heard the former empress had taken ill. She felt too much for that abandoned woman as well. If things had gone somewhat differently, Diana thought, that could have been her, living out her days in a similar exile.

She let out a breath and an unaccountable longing swept into her. The daffodils—pale and slim, ready to dance on the wind—would be popping up around Chauncey Castle. The neglected woods would smell of earth and spring rain. She rather missed the daffodils. But what did she want with such that rambling castle? It was an expensive pile at that, for the roof needed new leading, and the chimneys smoked dreadfully in the east wing, and the lanes all needed fresh gravel. It was good the lands had gone with the title to Chauncey’s cousin. He would need the income from the tenants just to keep that castle from crumbling. Better now to think ahead to London.

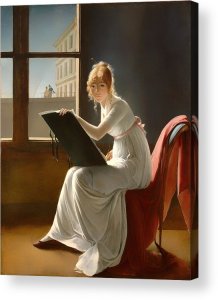

She would look to acquire a comfortable townhouse, perhaps in Berkley Square. That would give her a place where other ladies might call upon her. She could join a society or two, something musical and something charitable. Perhaps she would even take up sketching again.

She gave a snort at herself. So much domesticity! As likely to come about as it was for the devil to be kind. She would be bored silly within a season with such a tame life, wouldn’t she?

She turned her steps toward the river and let her stride lengthen. The Seine flowed through Paris in civilized curves. It struck her as a tidy body of water with arching, stone bridges crossing it like stitches. It lacked the size and depth of the Thames—no tall sailing ships lined the shore. No warehouses or docks stood along its edges. The small islands that lay like oblong scones in the river had been built upon for centuries with their stone houses and cathedrals. Notre-Dame’s square towers rose into the sky, dark from soot. Its bells would ring soon for morning mass of some kind. Another place she ought to visit, but not with the feel of cards still stiff in her hands and champagne light in her head. Besides, what would a good Anglican do in a Catholic church other than make herself an awkward tourist?

Her walk did nothing to settle her. However, she became aware of other steps behind her. At the next corner, she turned sharp and waited to see who followed.

Taliaris stepped from a swirl of morning mist like some phantom soldier after a battle. Unfair that he should look not an ounce fatigued by a long night. He stopped in front of her. The impluse danced inside her to swing up her umbrella and poke him in the chest with its tip and tell him to go to blazes. But Jules had said she must patch things.

Cocking her head to one side, she said, “We always seem to meet at the most inopportune moments.”

“I would not bother you, but you have no maid with you, no servant. No one in fact. Paris keeps uneasy company these days.”

“But the city is so very well guarded just now, and I can manage.” Diana waved her umbrella as she might a saber. “I have been doing so for any number of years.”

“Managing to get and lose a husband?” Giles asked, his voice a low growl.

He frowned at himself. He had told himself he would not pry. Yet, as soon as he had glimpsed her in the Jardin des Tuileries like some queen from the past, so certain of herself—seemingly unknowing that even queens could die—he had decided he must follow. Too many soldiers would think any woman on her own was no better than she should be, and he did not trust the manners of either the Prussians or the Russian.

Eyeing Diana and her umbrella—not much of a weapon that—he tucked her empty hand into the crook of his arm. She made no move to object. He started to walk her back the way she had come.

She glanced at him. “You make poor Chauncey sound no more than a glove I dropped. I assure you, it—”

“Was a love match? A passion that left you broken hearted?”

“Now you sound a cynic—and, well, no, it did not—” She broke off her words and bit her lower lip. The dawn bathed her in a pink glow. She looked the goddess now for whom she had been named, lush and proud. The years fell away. Giles could feel his mood softening. “He what, ma chère?”

She made a face and looked down to where she swung her black umbrella in step with her stride. “I hate complainers, so I do not intend to become one. And I ought to apologize. Another thing I hate. But I was in the wrong to strike you. I want to make amends.”

“Now you do not sound like a Frenchwoman. You sound too English. You look it as well, with your little bonnet and your long stride.”

“You, sir, are mocking me. No, do not waste your breath with a protest. You are. I can hear it in your tone. But tell me one thing and then I promise to leave the past be. Did you at least think of me over the years? Imagined me in Surrey, at Edgcot Place, sitting by a window, pining—”

“Never that,” he lied.

“Yes, pining. Probably sighing, too, and…and knitting, or stitching. They are the sorts of things men somehow think women are born knowing.”

“A huntress with domestic skills? You malign my imagination. No, I had you slaying hearts in ballrooms and—”

“Ah, so you did think of me,” Diana said, turning to face him, her eyes bright.

He pressed his lips tight. This was why one should not ask questions. The past was the past and should be left there. He lifted a shoulder and gave her as much of the truth as he could afford. “Do you think you did not leave your mark? I am certain many a man remembers you, much to his dismay.”

“Dismay? Nothing more?”

“Come now. We met by chance years ago. I managed to be of service to you and your aunt, and that knave with you.”

“Paxten Marset. He is now my aunt’s husband and utterly respectable, I shall have you know.”

“My felicitations to your aunt. I suppose I must give them late to you as well for the marriage you had.”

“Oh, no, not for that. I ought to have listened to my mother. I could have done far better than poor Chauncey in my earlier seasons. Why there was one year I had three proposals.”

“Three?”

His sharp question stopped Diana.

She widened her eyes and put a hand to her mouth as if she had let the words slip. She hadn’t. She wanted him to know she had once been quite the prize. The umbrella swung between them, dangling from her fingers. She pulled her hand down and jabbed the umbrella point forward, swinging it to indicate the path back into the formal gardens. “Perhaps we should save those stories for another time. We ought to manage some courtesy to each other this late in the day. Or is it early? Ah, I know. Let us start again.”

She pulled away from him. With both hands braced on the handle of the umbrella, she offered a smile and bobbed a curtsy. “Enchante. I am Diana, Lady Chauncey—Lady Chance to almost all. But I give you leave to call me Diana, for I feel we must be good friends.” She held out her gloved hand.

He looked at it. Lifting his stare to her face, he frowned. “This is absurd.”

“No, no. It is a new day. Let us not spoil it with an argument before breakfast.”

Mouth set tight, he took her hand and bowed. “Milady Chauncey.”

“And you, m’sieur, will you not introduce yourself?”

“No, I will not.” Tucking her hand back in place, he started walking. Diana had to hurry to keep up. “That is enough farce for the day.”

“Oh, no, we had the farce last night.” She leaned forward and peered up at his face. She made a show of examining the cheek she had struck. “At least you seemed to have come through this relatively unscathed. Well, M’sieur Mystery, if you will not give me your name in an introduction, which is already scandalous, for we should be proper about this and someone of good repute who is known to me ought to be making you known to me. But this is Paris. Why do you not tell me something of yourself and how you have kept over the years?”

He shook his head. “You wish to hear of the disaster of Spain? Or our disasters at least. Your great victories were not in your papers? Or do you wish to know of its heat and dust and bitter cold? Of mud and too much blood, and how the Emperor’s brother abandoned all at Vitoria? We lost not just the King of Spain but Spain that day—not a topic to sully a fresh dawn.”

“Well, then, let us talk of something else.”

He glanced at her. “Of why you are here in Paris, perhaps?”

“My, you are direct. But you must know we English have all been terribly cooped up upon our little island. I expect you shall soon be overrun with us. Although I know some hold back, for our last visits ended with abrupt departures, as you also know. Perhaps their caution is wise and I am the silly one to be so daring as to return with cannon powder still almost quivering in the air. I, however, wish to be among the first to improve my wardrobe. My cousin Jules assures me I shall dazzle London after this visit.”

“Yet another gentleman under your spell? Is he one of those you almost married?”

“What—Jules?” She smiled and swung her umbrella up and out again, slashing the air. “I think there are times Jules wishes for the right to beat me as only a husband may. But he resists all feminine wiles. He swears I am to blame for leaving him immune to fair charms. I used mine on him indiscriminately when we were both growing up—our family lands march together. And you must think I am a flirt with a dozen men after me to ask such a question.”

“I think things happen around you and to you.”

She wrinkled her nose. “I only wish that were true…m’sieur.” She stressed the word with a touch of mockery.

“If it is to be Diana, you had best leave off such formality. You know my name. I want you to use it,” Giles said, the words curt.

He knew he had no right to this sullen mood of his. But disappointment ate at him. She was not the girl he remembered. She was not that child of honor and courage she had seemed so long ago. The memory soured. He hated that. He took a breath and forced himself to be fair. The years had changed him as well. Why should they have left her the same as what he had…ah, but there was nothing here to mourn.

He shook his head. “I had best see you back to where you stay.”

She gave him her direction and he took her there, crossing over the Pont Marie to the Ile St-Louis. On the doorstep, she pulled away and stared at him. He could not read her expression. She smiled, but the curve of her lips looked stiff upon her face. He could feel the heat of her body. He could remember how she had once felt pressed closed to him.

“Thank you…Giles. I am certain you have saved me once again.”

“It grows chill. We shall have rain. And we have too many armies in paris. Think on that next time you go walking and bring something more than that to look after you.” He gesturing to her umbrella. With a short bow, he, but he could feel her stare upon his back as he strode down the street.