In this modern era, we’re accustomed to a huge variety of foods year ’round—we have freezers for storage, air shipment to move food from one hemisphere to the other in any season so the usual fruits and the expected veg are always in stock, and we always have canned good. This was not the case in the Regency-era England.

While there was some cold storage in ice houses, and meat could be hung to be aged, the art of food storage was time consuming. It required skill, space, and money enough or land enough to purchase or grow the food. The most common means to store food were the age-old ways to pickle, salt, or dry. Canning food wouldn’t really take off until the mid 1800s—and would start off being an ordeal to get any sealed-with-lead can open. This meant the seasons mattered when it came to food.

For meats, besides beef and mutton which the English always seemed to have, there might be what was called “house-lamb” or lambs born late in the season and kept inside. Pork was a staple for many, as pigs were low cost to raise. Wild boar could also be had in the country-side. Venison might be served, if you had the land to hunt, and it was no longer held that all the deer belonged to the king. Goose was cooked for more than just the Christmas meal, and there would be turkey, pigeons, chicken, snipes, pheasant, duck, guinea-fowl, woodcock, larks, guinea-foul, and grouse to eat. Dotterals, or a type of plover, could be eaten (also came to mean an old fool), and widgeon, a fresh-water duck, another word with a double-meaning, coming to mean someone feather-brained.

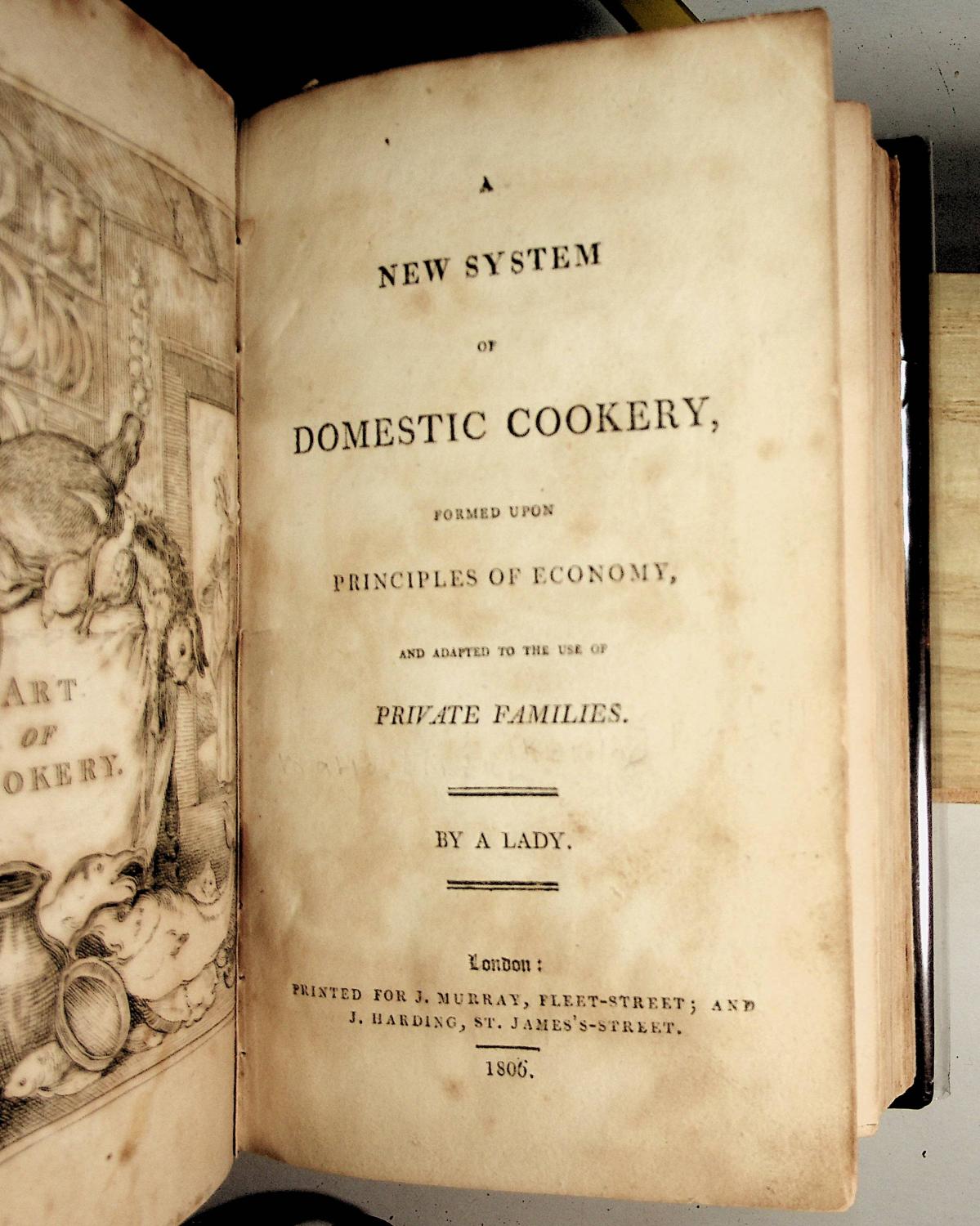

Rabbit came into season in January, and in February there might be duckling, and chicken is noted as by Mrs Rundell in her book Domesty Cookery as “are to be bought in London , most, if not all, the year, but are very dear.”

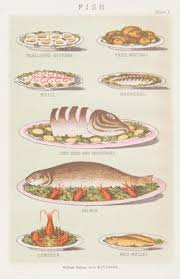

The months ending in “R” held that these were the months for shellfish, and cold months meant seafood would be kept cold as it was transported, so long as the roads weren’t blocked by snow or mud. Cod, turbot, soul, sturgeon, gurnets, dories, and eels joined the list of fish in season in December. Gudgeon might mean a person easily fooled, but it was a small whitefish often used for bait, and was eaten.

Lobster came into season in January, as did crayfish, flounder, plaice, perch,smelts, whiting, prawns, and crab. Oysters were very popular with the English, with oyster houses in London. Oysters were cheap, plentiful and even sold on the street.

Winter was the time for root vegetables such as: leaks, onions, shallots, carrots, turnips, parsnips, beets, and potatoes. Hardy vegetables—and those from hot houses—included cabbage, spinach, cress, chard, endive, cress, lettuces, and herbs. Herbs could also be dried. Some of the vegetables that are not so common now were in season in the winter, including: skirrits, a white root vegetable similar to a parsnip; scorzoneras or black salsify, which is said to taste similar to asparagus or to oysters; cardoons or artichoke thistle, which tastes like an artichoke but you eat the stems.

Nuts are another crop easily stored, and were gathered in September. Walnuts and chestnuts would be available in winter and are native nut trees in England, along with hazelnuts. Acorns from oaks were consider a food fit only for pigs. Beech trees also produced a nut, but they’re tough and more work than considered worth the time. Other non-native nuts were not as popular and are not noted in many recipes from the era, although they could always be imported by those with the money and interest.

Forced asparagus added a delicacy to the usual winter vegetables, and could start to arrive in later winter. Stored apples, pears, and preserved summer fruit appeared on the better, richer tables. Besides the dried or stored fruit, the rich might have hot houses that might produce oranges, grapes, and pineapples, which had arrived in England in the 1600s. There were also medlars and bullace. The medlar is a member of the rose family and produces a brownish fruit that appears in winter and which can be eaten raw like an apple or used in recipes. It has been cultivated since Roman times. The bullace is another member of the rose family and is also called a wild plum. It can be used to make bullace wine, or can be used for pies, but was out of season by December.

By late winter, preserved fruits would be running low in all but houses with large orchards or those with greenhouses that could force fruits. Stored apples and pears would have to serve for families and guests until the expensive forced strawberries of February appeared.

December was also the month when all events seem to lead up to Christmas. Around the third century there was an attempt to fix the day of Christ’s birth by tying it to a fesival of the Nativity kept in Rome in the time of Bishop Telesphorus (between 127 AD and 139 AD). While it was believed the Nativity took place on the 25th of the month, which month was uncertain and every month at one time or another has been assigned as Christ’s mass. During the time of Clement of Alexandria (before 220 AD) five dates in three different months of the Egyptian year were said to be the Nativity. One of those corresponds to the December 25th date. Although various dates were questioned for several generations by the Eastern Church, the Roman day became universal in the fifth century.

First reports of people bringing holly and pine branches into their homes at Christmas-time date from the late Middle Ages. Symbols of life in the dead of winter were placed on windows, mirrors, and in vases, and may have served to keep evil spirits away. Over time, this mythical function of the greens became simply decorative. Evergreen ropes (garlands) were draped over staircase railings, mantels, picture frames, and along ceilings. Fearful that dry branches would catch fire from oil lamps or sparks from the fireplace or heating stove, families waited until almost Christmas Eve to hang the garlands.

Christmas cakes, puddings and mince pies are traditional foods of the season. According to one variation, plum pudding—an old English holiday treat—gets its name not from plums, but from the process of “plumming” meaning raisins and currants are plumped up by warm brandy then molded with suet and a bit of batter.

According to the Oxford Companion to Food, “…Christmas pudding, the rich culmination of a long process of development of ‘plum puddings’ which can be traced back to the early 15th century. The first types were not specifically associated with Christmas. Like early mince pies, they contained meat, of which a token remains in the use of suet. The original form, plum pottage, were made from chopped beef or mutton, onions and perhaps other root vegetables, and dried fruit. As the name suggests, it was a fairly liquid preparation: this was before the invention of the pudding cloth made large puddings feasible. As was usual with such dishes, it was served at the beginning of the meal. When new kinds of dried fruit became available in Britain, first raisins, then prunes in the 16th century, they were added. The name ‘plum’ refers to a prune; but it came to mean any dried fruit. In the 16th century pudding variants were made with white meat…and gradually the meat came to be omitted, to be replaced by suet. The root vegetables disappeared, although even now Christmas pudding often still includes a token carrot…By the 1670s, it was particularly associated with Christmas and called ‘Christmas pottage’. The old plum pottage continued to be made into the 18th century, and both versions were still served as a filing first course rather than as a dessert…”

Mince pies made from mincemeat, which originally had meat in it but shifted from a savory to a sweet, were another traditional fare, with the tradition being that everyone in the household should stir for luck. From the Middle Ages and on it became common to stretch the meat in the pie or mincemeat by adding dried fruit. The reduction in meat continued until only beef suet was left in the mincemeat.

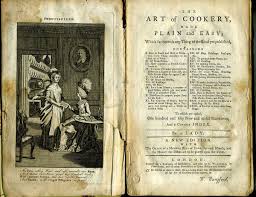

In The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy in the mid 1700s, Hannah Glasse gives this recipe:

“Take three Pounds of Suet shread very fine, and chopped as small as possible, two Pounds of Raisins stoned, and chopped as fine as possible, two Pounds of Currans, nicely picked, washed, rubbed, and dried at the Fire, half a hundred of fine Pippins, pared, cored, and chopped small, half a Pound of fine Sugar pounded fine, a quarter of an Ounce of Mace, a quarter of an Ounce of Cloves, a Pint of Brandy, and half a pint of Sack; put it down close in a Stone-pot, and it will keep good four Months. When you make your Pies, take a little Dish, something bigger than a Soop-plate, lay a very thin Crust all over it, lay a thin Layer of Meat, and then a thin Layer of Cittron cut very thin, then a Layer of Mince meat, and a thin Layer of Orange-peel cut think over that a little Meat; squeeze half the Juice of a fine Sevile Orange, or Lemon, and pour in three Spoonfuls of Red Wine; lay on your Crust, and bake it nicely. These Pies eat finely cold. If you make them in little Patties, mix your Meat and Sweet-meats accordingly: if you chuse Meat in your Pies, parboil a Neat’s Tongue, peel it, and chop the Meat as finely as possible, and mix with the rest; or two Pounds of the Inside of a Surloin or Beef Boiled.”

Gingerbread cakes were also a common holiday treat that had come to England from Germany. Seven Centuries of English Cooking gives this recipe adapted from Hannah Glasse’s book:

- 1 lb. (3 1/3 cups) Flour

- 1 Tsp. Salt

- 1 Tbsp. Ground Ginger

- 1 Tsp. Nutmeg

- 6 oz. (3/4 cup) Butter

- 6 oz. Caster (confectioner’s) Sugar

- 3/4 lb. (1 cup) Treacle (or Corn Syrup)

- 2 Tbsp. Cream

(Note: She gives tablespoon as Tabs, but this has been changed here to the more common tbsp.)

Eggnog possibly developed from a posset, or a hot drink in which the white and yolk of eggs were whipped with ale, cider, or wine. The nog in the name came from a noggin, or a small, wooden mug. It was also called an egg flip from the practice of rapidly pouring the drink to mix it, or flipping the drink. It was a rich drink with milk, egg, brandy, madeira or sherry and fit for any celebration but came to be associated with Christmas.

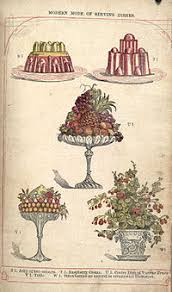

Trifles are also traditionally associated with Christmas, although they might be had for any special occasion in the Regency, or any elegant dinner. Elizabeth Raffald included a trifle recipe that is very modern sounding with macaroons, wine, cream, and sugar. The difference comes from adding cinnamon and “different coloured sweetmeats” which are not generally found in modern trifles.

Another English tradition were sugarplums, a confection traditionally made from sugar-coated seeds. The earliest mention dates to 1668. The Oxford Companion to Food also lists comfits as, “…an archaic English word for an item of confectionery consisting of a seed, or nut coated in several layers of sugar…In England these small, hard sugar sweets were often made with caraway seeds, known for sweetening the breath…”

Cakes of all shapes and sizes were included at festive holiday rituals long before Christmas. Ancient cooks prepared sweet baked goods to mark significant occasions. Many Christmas cookies we know today trace their roots to Medieval European cake recipes. According to foodtimeline.com, “By the 1500s, Christmas cookies had caught on all over Europe. German families baked up pans of Lebkuchen and buttery Spritz cookies. Papparkakor (spicy ginger and black-pepper delights) were favorites in Sweden; the Norwegians made krumkake (thin lemon and cardamom-scented wafers).”

Foodtimeline.com also notes, “The fruit cake as known today cannot date back much beyond the Middle Ages. It was only in the 13th century that dried fruits began to arrive in Britain…Early versions of the rich fruit cake, such as Scottish Black Bun dating from the Middle Ages, were luxuries for special occasions. Fruit cakes have been used for celebrations since at least the early 18th century when bride cakes and plumb cakes, descended from enriched bread recipes, became cookery standards…”

Households also celebrated not just according to the season, but also to the customs of the area. In the Regency, local customs in the countryside might well be used for the celebrations.

For one of my books, Under the Kissing Bough, I needed a Christmas wedding and customs that suited the countryside around London. In ancient days, a Christmas wedding would have been impossible for the English Church held a “closed season” on marriages from Advent in late November until St. Hilary’s Day in January. The Church of England gave up such a ban during Cromwell’s era, even though the Roman Catholic Church continued its enforcement. Oddly enough a custom I expected to be ancient—that of the bride having “something borrowed, something blue, and a sixpence in her shoe”—turned out to be a Victorian invention.

English Christmas customs are those carried down through the ages: the Yule log from Viking winter solstice celebrations, the ancient Saxon decorations of holy and ivy, and the Celtic use of mistletoe on holy days, which transformed itself into a kissing bough. The wassail bowl—a hot, spiced or mulled drink—was another tradition left over from the Norse Vikings.

Celebrations continued to mix tradition and religion when the Twelfth Night feast arrived on January 5, which combine the Roman Saturnalia with the Feast of the Epiphany, when the three wise men were said to have paid tribute to the Baby Jesus.

In Edinburgh, Scotland, Hogmanay is the special New Year’s celebration. But Twelfth Night celebrations for the Epiphany (when the wise men came to see the baby Jesus) are the big event. This is followed by Plough Monday, which is the traditional start to the new agricultural year. Since there’s not much work for a farmer in the winter, plough men would blacken their faces and drag a decorated plough through town asking, “Penny for the ploughboys.”

Molly dancers (a black faced Morris dancer) also came out in East Anglia on Plough Monday. And many towns, such as Whittlesey, had the tradition of men or boys dressing up as Straw Bears to add to the entertainment.

Shrove Tuesday fell in February (the last day before Lent begins on Ash Wednesday). Traditionally, Shrove Tuesday was the day to indulge, so pancakes were a traditional food as the butter, fat and eggs might all be things to give up for the forty days of Lent.