Shopping. Parties. Fashion. Frivolity and pleasurable pastimes. Much of Regency fiction presents ladies indulging in such a life. But a married woman also had responsibilities–and the greater the household under her care, the greater her duties.

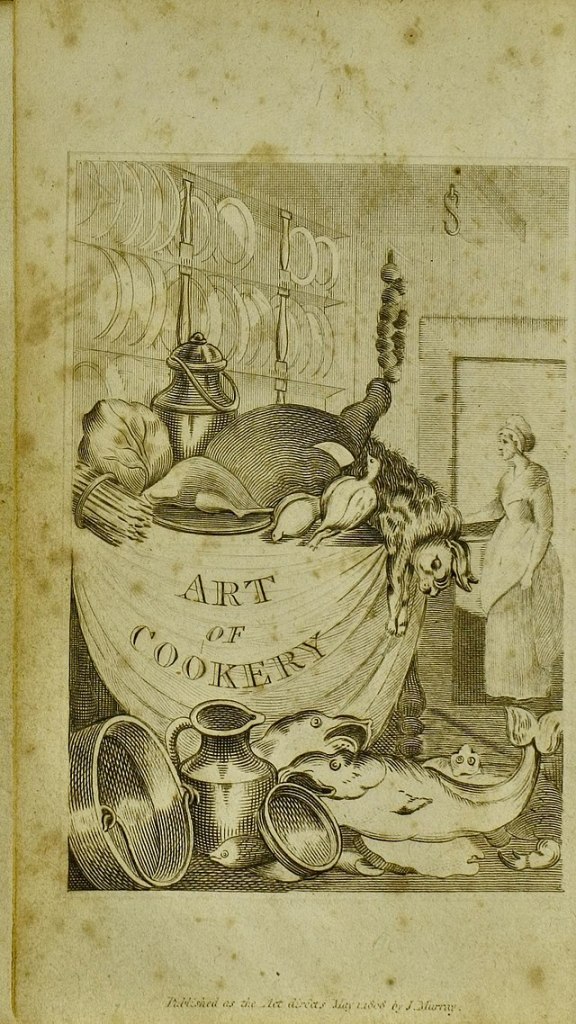

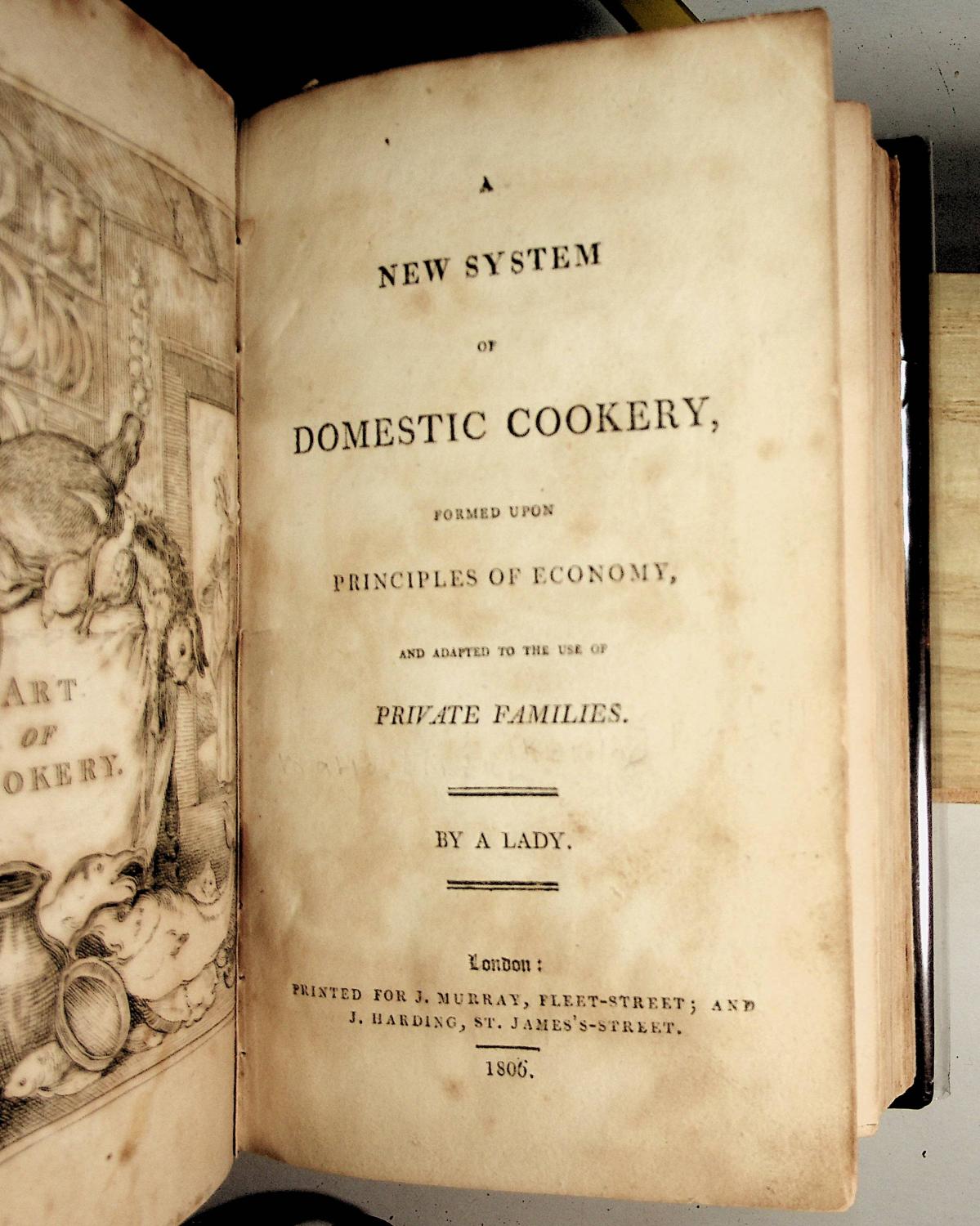

Maria Rundell in her book Domestic Cookery (1814 edition) recommends that the most important aspect of a girl’s education is the addition and subtraction of numbers. Without these, she cannot possibly keep the household finances, account for purchases by the staff, and budget her expenses. She also holds that March’s Family Book-keeper “is a very useful work, and saves much trouble in the various articles of expense–being printed with a column for every day of the year so that at one view the amount of expenditure on each, and the total sum, may be known.”

If married to a lord with multiple properties, a lady might be expected to manage all his estate households. She would be assisted by housekeepers, but it would fall to her to review accounts and hire the household servants, for while her lord might be concerned with properties, society dictated that the house was a lady’s domain.

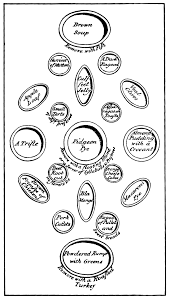

The English class system extended not just through the upper ranks, but well into lower orders, which had its own complications of hierarchy. In the country, an estate needed the following, in order of their own precedent:

A land steward to manage the estate, collect rents, and settle disputes between tenants. His salary would be variable, based on his experience and his tasks—the land steward to a great estate such as a dukedom would have a handsome salary, even up to five hundred pounds a year.

A house steward or housekeeper to supervise indoor staff for two hundred pounds a year, and some houses might have both a house steward and a housekeeper who served under him.

A valet for the master of the house, and a lady’s maid for the lady of the house, whose wages might be anything from twenty to two hundred pounds a year, depending on if they were in demand in London, or stuck in the countryside without opportunity.

A master of horse or stable clerk to supervise the stables, including livery servants who worked outdoors, coachmen, and stable lads, for around sixty pounds a year in salary.

A butler, a cook, a head gardener, who earned twenty to forty pounds a year each. The house might also include a wine-butler, and also a porter or major domino who supervised the comings and goings at the house, and a groom of chambers, who looked after the furniture in the house.

In the lower male ranks came other coachmen, footmen, running footmen, grooms, under-butlers, under-coachmen, park-keepers, game-keepers, yard boys, hall boys, and footboys.

In the lower female servant ranks came nannies, chambermaids, laundry maids, dairy maids, maids-of-all-work, and scullery maids.

In town lower ranking staff might earn as much as ten to twenty pounds a year each, with men being paid more. In the country, salaries were half that or could be even less.

Between servant and master existed those creatures who might be of upper or lower class, but who did not quite fit either: the governess, tutor, and dancing master. Which is one good reason why these positions were often uncomfortable–you couldn’t be one of the servants and you weren’t quite one of the quality. (Any time you had to take a job you pretty much fell out of the ranks of the upper class.)

With such a social structure, an estate acted very much like its own village, with squabbles between servants, gossip, flirtations, jealousies, and structure. A large estate might require as many as fifty indoor servants, and twice that or more in outside labor to deal with the estate’s lawns, animals, produce, beer-making, dairy and so on. However, the world was changing.

New factories, new roads, and lower costs of transportation were making even the servant class more mobile. And keeping a good staff began to be an issue.

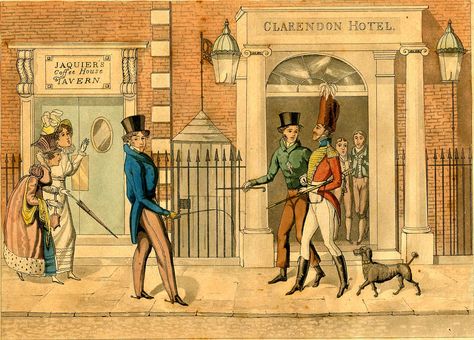

To hire staff, the lady of the house–or the housekeeper or house steward–might advertise in The London Times or the Morning Post. The custom of ‘Mop Fairs’ where servants might parade and find new positions also existed through the 1700’s and into the 1800’s. “Females of the domestic kind are distinguished by their aprons, vs. cooks in coloured, nursery maids in white linen and chamber and waiting maids in lawn or cambric,” writes Samuel Curwen of such a fair at Waltham Abbey in 1782. Such a fair included strolling, stalls, and full public houses, with a good bit of drinking. It was, for many servants, a holiday.

Dress very much told of a person’s status, both as in the world upstairs and below. The upper servants dressed in livery and uniforms provided by the house, while lower servants were expected to wear plain and ordinary.

The cost to hire, feed, and dress an extensive staff could be considerable. Wages tended to be higher as well in a richer house. And servants could expect to be left tips–or vails–by visiting guests. A vail might be as much as a month’s wages left by a departing houseguest, the amount determined by the status of the guest and the rank of the servant.

Coupled with the expense of a staff came its management. While on many country estates, servants came from the local lower orders and might well be born on the estate and look to live and die there, in town, servants looked for opportunities to advance. Servants in town could register with agencies, but they would need to bring with them good references.

However, as noted by a Portuguese visitor to England in 1808, “servants are not to be corrected, or even spoken to, but they immediately threaten to leave their service.'”

As with any group, problems arose. Servants gossiped, stole from the pantry, and took items to sell from a careless master’s closet, and then there was the issue of upper class males taking too great an interest in lower class females.

“If you are in a great family, and my lady’s woman, my lord may probably like you, although you are not half so handsome as his own lady.” So wrote Jonathan Swift in his “Directions to Servants” in 1745. He went on to advise any lady’s maid to make certain she is paid for “the smallest liberty.”

Maria Rundell notes that, “Instances may be found of ladies in the higher walks of life, who condescend to examine the accounts of their house steward; and by overlooking and wisely directing the expenditure of that part of their husband’s income which falls under their own inspection, avoid the inconvenience of embarrassed circumstances.”

Of course, a lazy or ignorant woman might leave all management to her housekeeper, cook, and other servants, but she did so at the risk of being cheated by her staff or by merchants. For a woman dealing with great houses, all this jotting down of expenditures could be left to a house steward, a secretary, or a housekeeper. But there were numerous stories of servants who filled their pockets by padding the household account books, writing in more than was paid to the merchants and keeping the difference. A lack of knowledge in a very large household could easily lead the family into financial difficulties. The Duchess of Devonshire, with her fashionable excesses, her addiction to gambling, and her utter lack of any financial knowledge, constantly exceeded a generous allowance, borrowed heavily from everyone, and left behind debts of around twenty thousand pounds, which had to be settled from the family estate.

On the other end of the spectrum were ladies so thrifty that they watered the wine that they served at parties, underpaid their staff, and accounted for every half-penny spent.

A woman in ’embarrassed circumstances’ might need to know how to stretch her pence for food. In the city, she could buy meat scraps rather than full roasts, but there would be no funds for luxuries such as butter. The cheapest bread would be coarse, adulterated with alum, which cost less than flour. And she might be able to afford wool for knitting gloves and scarves and undergarments and fabric to make clothes, or she might have to make do with purchasing used clothing from a street fair. Shoes would need to be bought, and tinkers paid to mend pots and sharpen knives. With the added expense of rent, anything such as costly tea would be a luxury, as would any servants or services.

In the middle class, a woman could count on more luxuries. She would have staff to do the work, and could afford beeswax candles that did not drip (or smell of beef fat), and fine milled soap. There would also be funds to pay the washer woman, the school fees for her children, buy coal and wood to heat her house, pay servant’s wages, donate money for charity, and hand out coins as tips when she visited country houses.

For any lady of a great family, launching your children into the world could be rather like managing a small corporation. It’s no wonder parents expected such investments would pay off with alliances that brought influence and money back into the family. No wonder, too, at the appeal of living quietly in the country where such demands were not made upon the purse.