Back a few years ago, I wrote this article for RWA’s Beau Monde’s newsletter. Since horse information doesn’t really go out of date, here it is again, for folks who need to write about horses. Somewhat edited.

For those whose equine experience has been rather limited, this might offer some practical information you can use when your characters have to have some real horse sense.

General Horse Sense

The sexes of horses include: mare, stallion, gelding which is a castrated male horse. Baby horses are called foals, with filly for a girl, and colt for a boy. Horses usually mature between ages five to seven.

Horses are creatures of habit and herds. Despite movies you may have seen, the herd is actually governed by a head mare. The stallion is there to protect, she leads.

A horse would rather run from trouble than fight, and so a horse will only fight if it is cornered. Horses are made into vicious animals only by abuse.

For a good source on horse behavior, I recommend Mind of the Horse by Henry Blake. It gives excellent information on a horse’s eyesight–which is designed to see long distances and up close for grazing, on how to read horse communication–which all occurs with nickers, ear positions, and posturing.

As creatures of habit, horses love to maintain the same pattern. There are many stories of horses knowing the way home to the barn, of work horses doing the same work every day–even after they are retired.

Horses eat hay and grains, or what the English call “corn.”

Corn includes barley and oats. Hays include oat hay, timothy. They don’t feed much alfalfa in England, it’s a hay that grows wonderfully in the western states, but not so well in England. Horses do not eat straw–you hope not, at least. They are bedded down on straw.

Horses also come in all variants of brown, with true black and white being the rarest colors. Horse colors sometimes have specialized names, such as: seal bay (a dark brown with black legs, tail and mane), liver chestnut (a dark red chestnut), roan (which can be blue or strawberry), dun (what we call buckskin in the States), and even piebald or skewbald (what we call paints).

Horses have four basic “gaits” or paces: the walk (a four beat movement), the trot (which is two beats), a canter (a three beat gait), and the gallop (four beats).

A fit horse can travel 25 – 100 miles in a day, at various paces. The trick is to rest the horse with walking between. It is possible to do more, but you will be putting stress on the horse, and could possibly damage him.

Speeds for horses vary, for it depends on the horses’ size, fitness, and what he is carrying. A team of six horses pulling a light carriage will go faster and farther than a single horse pulling a very heavy wagon. A good source for traveling times is to check mail coach times.

Some useful terms to know include: near side (left side), far side (right), hind quarters (back of the horse), forehand (front of the horse).

On a carriage, the leaders are the front team, and the wheelers are the back team.

Horses can be drive as a single horse, a pair, a four-in-hand (and that does mean holding all those reins in one hand), a team of six, a tandem (one horse in front of the other), or Unicorn style (three horses, one in the lead, two as wheelers).

English equipment also has its own vocabulary, and so it’s important to know the English words (rather than the western phrases).

To ride, you would use: saddle, girth, bridle, bit, and stirrups–which are made up of stirrup irons and stirrup leathers. The back of the saddle is the cantle, the front is a pommel. There’s no saddle horn on an English saddle.

Do keep in mind that riding styles have change over the last two hundred years. Modern English riding comes from the forward seat, developed in the early 1900’s. We ride with a shorter stirrup, leaning “forward” to go with the motion. Riders of the 1800’s leaned back and rode with long stirrups that kept their seat in the saddle–even jockeys rode sitting down square on a horse’s back. Studying sporting prints of the era will give you lots of information– but make sure the drawings are not caricatures.

In the stable the horse wears a headcollar (not a halter, as we call it in America).

A carriage horse is in harness, usually between carriage shafts.

The aides to control a horse include the legs, meaning the calves and heels. Voice (cluck or whoa, not giddyup), hands, the whip and spur. A hunting whip actually is a special design with a crook on the end to open gates, and whip points on the end you can change to actually use to control the hounds. The whip is not actually used to whip the horse.

A lady will often use a whip to give commands to the horse on the ‘off’ side, since her legs hang down on the ‘near’ side. The whip here is used to just tap the horses’ side.

Horses have been bred for specific function for centuries. There are hundreds of breeds, but there are also some generic terms for horses used for specific purposes.

Hack – a city riding horse, can also be called a cob.

Hunter – a strong boned, good jumping horse.

Carriage Horse – a strong horse with showy action (not necessarily rideable, or a good ride).

Ladies’ Horse – a comfortable, smooth riding horse.

Now, how much would a good hunter or hack cost you in Regency England?

To put it into perspective, think of horses as cars–the more status, the more they cost.

John Tilbury of Mount Street in London offered a horse for rent at 12 guineas a month. For 40 guineas, you could get two hunters and a servant. (He also gave his name to a carriage he designed–the Tilbury.)

The average value of a coach horse in the Regency era was 20 pounds. A hunter or race horse might go for anything from 20 pounds to 1,000 guineas.

On 5,000 a year, family could keep 22 servants, 10 horses, and three carriages–so long as they weren’t spending 1,000 guineas per race horse bought.

Carriages were even more expensive than horses.

In Northanger Abbey, Mr. Thorpe enthuses over his new curricle, boasting: ‘Curricle-hung, you see; seat, trunk, sword-case, splashing-board, lamps, silver moulding, all you see complete; the iron work as good as new or better’ — and all for fifty guineas.

Chandros Leigh, a distant cousin of Jane Austen, obtained an estimate for a fashionable landau in 1829; the price of the basic carriage was 250 pounds, which included, ‘plate glass and mahogany shutters to the lights, and plated or brass bead to the leather, lined with best second cloth, cloth squabs, and worsted lace….

The ‘extras’ he ordered, including footman’s cushions, morocco sleeping cushions, steps, silk spring curtains, his crest on the door, embossed door handles and full plated lamps brought the cost to 417 pounds, 11 shillings and six pence, but he was given 60 pounds in exchange for his old carriage.

But what is the difference between a hack and a hunter, or a race horse?

Many of the modern horse breeds existed in the Regency. General horse breed types include:

Ponies – less than 14.2 HH – often used by ladies in pony carts or carriages, or for packing goods — they’re smart, sturdy, good ‘doers’ (they get fat on very little food)

Cobs — Often a cross with TB and Pony — usually 13 – 15 HH – often a ‘hacking’ horse, or a light city riding horse.

Cold Blooded Horses – Draft horses. Used mostly in farm work, and later in factories.

Warm Bloods – Often crosses of Hot Blood to cold Blood. Used as carriage horses, and good military horses, for pulling cannon and what not.

Hot Bloods — Arabian and Thoroughbred. Used for racing, and in general showing off. Arabians were very exotic as they were hard to come by. They tend to be smart, sturdy horses with great endurance. When crossed with English mares, they produced tall, athletic horses which we’ve come to know as Thoroughbreds.

All Thoroughbreds trace back to three breed establishing stallions.

The Darley Arabian, Manak, came to England in 1703. I actually lived in the house owned by the family who had imported him. They had a life-size portrait in the main hall. The portrait seemed a little stiff, and that was because it was traced directly from the horse–after he had died. He was quite a small horse, even by today’s standards of Arabians.

The Godolphin Barb came from Paris to England in 1738. He was a gift from the Bey of Tuins to Louis XV, but he was ill-valued and ill-treated and sold off as a cart horse. Eventually was sold to Lord Godolphin, who took him home to England and set about producing excellent race horses.

The Byerley Turk–most likely an Arabian–was a war-horse acquired by a Captain Byerley.

These stallions produced, when crossed with English mares Matchem, Herod and Eclipse–racing stallions who can also be found in the ancestry of every Thoroughbred.

The Racing World

Racing in the Regency was only for the very rich. The Prince Regent’s racing stud farm came to cost him 30,000 pounds a year.

While racing can be traced back as far as English history goes, it’s modern form really comes out of the 1700’s.

In 1711, Queen Anne established regular race meetings at her park at Ascot.

Racing continued rather unorganized and unregulated. Gentlemen organized races for themselves, often “matching” particular horses against each other. By 1727 a regular Racing Almanac began to be printed.

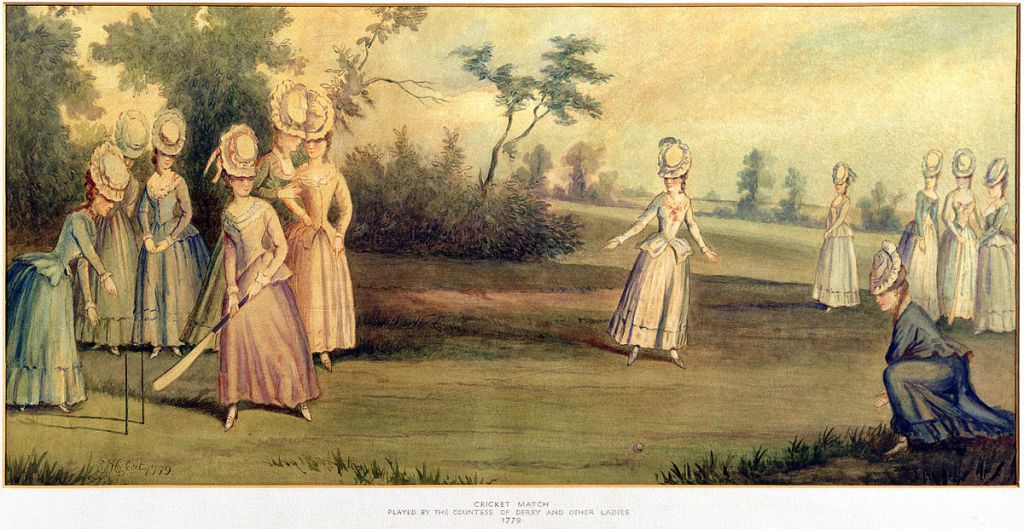

Flat and jumping races were also held for women only. Mrs. Bateman wrote in 1723, “Last week, Mrs. Aslibie arranged a flat race for women, and nine of that sex, mounted astride and dressed in short pants, jackets and jockey caps participated. They were striking to see, and there was a great crowd to watch them. The race was a very lively one; but I hold it indecent entertainment.” This sort of attitude continued, but those women–such as the infamous Letty Lade–who did not care about their reputations rode and drove to please themselves, but they were the exception in the Regency world.

Around 1750, the Jockey Club comes into being, as a loose organization founded by gentlemen who regularly met at the Red Lion Inn at Newmarket. By 1758 the first regulation–for the weight of jockeys–was issued and the Jockey Club became responsible to the Crown for its organization.

In May of 1779, the first Derby was held. Initially, it was called “The Oaks” after the name of the hunting Lodge in Surrey, owned by the then twenty-seven-year-old Edward Smith-Stanley, 12thEarl of Derby. It became “The Derby” after the Earl won the coin toss to see whether the race would be named after him or Sir Charles Bunbury. Bunbury got his revenge in that his horse–Diomed–won the first Derby in 1780.

In 1791, the Jockey Club issued the “General Stud Book”, and by the early 1800’s Jockey Club stewards were at every racing meet.

In 1807, George III gave away the first gold cup at Royal Ascot. Also that year, Prince George quit racing after there was an accusation that his jockey, Sam Chiffney, was involved in dealings to fix a race. The prince was never a good looser.

Racing meet sprang up– and still run–at Newmarket in April and October, York in May, Epsom, Ascot in June, Goodwood, Doncaster, Warick, Manchester, Liverpool, Chester, Cheltenham, Bath, Worcester, and Newcastle.

Assize-week was the time for races, for it was when the gentry came into the chief town of the shire for trials, for selling harvest, and for races.

Steeplechasing–or what we know as races over fences–started off much slower and less organized than flat racing.

In the mid 1700’s, steeplechases were literally races between one church steeple to the next — over whatever lay in between.

By 1792 a race for 1,000 guineas was recorded near Melton Mowbray to Dalby Wood, covering about nine miles. But it was not until the 1840’s that Steeplechases began to be held over organized courses. They tend to remain informal races between individuals who want to try out their own hunters.

In both flat racing and Steeplechasing, do remember that England races clockwise–not counterclockwise as are horse races in the US.

But fox hunting is very similar to both the US and England.

In the Country: Hunting and Hacking

The record of the oldest English foxhunt dates back to mid 1600’s and the second Duke of Buckingham, who hunted the Bilsdale pack in Yorkshire dales. November to March is fox hunting season. It starts after the fall of the leaf…. it’s when the fields lie fallow. And it ends after the last frost and before the first planting.

Each hunt is composed of a Master– usually the man who owns the hounds. The Master may employ “whipper-ins” to help keep the hounds together. Hunting is informal in the 1700s–anyone can join in to follow the hounds (as in that wonderful scene from the movie Tom Jones when the Squire cannot resist the call of the huntsmen’s horns). Those horns are actually signals to the other huntsmen and the pack as to where the fox is headed.

The Duke of Bedford’s hounds hunted actually stags until 1770’s. But by 1780’s fox hunting took over in popularity. Enclosure Acts and reduction of forests mean less stag hunting. And hare hunting was generally regarded as more a necessity of country life.

Hunt territories varied widely. The fifth Earl of Berkely hunted an area from Berkley Castle to Berkley Square, stretching 120 miles. Most hounds were kept by rich individuals, and they often invited local farmers to hunt with them, for very often you depended on the locals allowing your hunt access over their farms—there’s still no way to predict which way a fox will run.

By 1810, there were only 24 subscription packs–or packs that you could pay to belong to and hunt, as opposed to requiring an invitation from the Master. But this would double, so that by the mid 1800’s hunting became a more a matter of ‘subscribing’ in exchange for the right to hunt with the pack.

The golden age for hunting in Leichesterchire is 1810 – 1830. This starts off with Hugo Meynell, who hunted his foxhounds from Quorn Hall in Leicstershire from 1753 to 1800. His record run was 28 miles in two hours 15 minutes.

During this time, there’s as many as 300 hunters stabled in Melton Mowbray–with some gentlemen keeping up to 12 hunters. You could hunt six days a week with the still famous packs–the Quorn, the Cottesmore, the Belvoir, the Pytchley. Lord Sefton, Master of the Quorn from 1800-02, went through three horses a day–which is why you might need a dozen horses.

Ptychey’s record run was in 1802, when the pack covered 35 – 40 miles in four and a quarter hours. With horse medicine being about the same as for people–horses were bled after a long, tiring day. So the life of a hunter could be a short, hard one. In Warwickshire, a hunter might fetch 200 – 500 guineas. But in Leichestershire, a hunter could cost up to 800 guineas

Wellington’s officers took to hunting in their regimental scarlet coats. These started to be called hunting pink (the story goes that this was after the tailor Mr. Pink, but there’s no evidence this is true). Each hunt, however, has its own colors–a color of leather boot tops, coat color and collar color and even button design. It’s said that Brummell never hunted past the first field, for he hated to get his white-leather boot tops muddied.

Ladies were also found in the field. Mrs. Tuner Farley hunted for 50 years. Lady Salisbury was master of the Hatfield Hunt from 1775 – 1819. She hunted old and blind, in her sky blue habit, with a groom leading her horse and yelling at her to, “Jump, damn you, my lady.” From 1788 to 1840, Lord Darlington hunted his own hounds four days a week in Yorkshire and Durham, with his three daughters and his second wife, all in their scarlet habits.

But between late 1700’s to about mid 1800’s, when the jumping pommel was invented for the side-saddle, ladies were more the exception than the rule, and they were more likely to be advised to “ride to the meet and home again to work up an appetite.”

Traditionally, each hunt always has a designated meeting place–a gate, or an inn, or even a house. You meet, the hunt cup is taken–folks drink to stave off the cold. You might meet around 11 and hunt all day–or until it’s dark. Bad weather does not stop hunting–wet weather means the scent will be high (so long as it’s not pouring). Ice can be dangerous–that’s when you get broken necks and legs.

A hunt really is lots of standing around, with bits of galloping to and fro. Trotting from cover to cover, hoping to draw a fox. Some hunts kept tame foxes they could let go if the day’s sport proved too slow. Some areas had to curtail their hunting to allow the fox population to come back.

Hunting was always viewed as a sport for everyone, but the reality was that it cost money to keep a pack of hounds and hunt them. However, anyone could take a horse and follow, if the master allowed it, and some followed the hunt in their carriages.

In Town: Hacks, Carriages and Hyde Park

Carriages for country and for town were generally quite different in build, for they served different purposes.

This was the pre-mass-production era–everything was custom built, or was bought second hand. Because carriages were often built to the owner’s specifications, they often acquired the owner’s name–as in a Stanhope Gig. One of the main places to have a carriage built was Longacre in London.

Types of carriages included:

The Phaeton – four-wheeled owner driven vehicle fitted with forward facing seats.

The Gig – two-wheeled vehicles (Whiskey), built to hold two.

The Curricle – which acted as the “gig” of the quality, and was built to hold two, sometimes with room for a goom behind.

A Town Coach – could be drawn by one or two horses (a pair).

Landau – held up to four people, and was drawn by a pair.

Barouche – could be drawn by a pair, or a team (four or six horses). Had an option for a driver, or for post boys to ride and control the horses.

A “Drag” was a slang term for a gentleman’s private coach. It was built much like a mail coach, and often used for race meetings or other outdoor events as it height and roof seats created its own grandstand.

In 1808, Mr. Charles Buxon founded the Four Horse Club, its members drove barouche carriages and so was also called the Barouche or Whip club.

Another driving club was the Four-in-Hand Club. The club assembled at George St., Hanover Square and drove to Salt Hill to the Windmill Inn. The pace was never to exceed a trot. Lord Barrymore could often be seen driving his matched grays, and he was also one of the founders of the Whip Club as well a member of the Four-in-Hand.

In 1805, smaller coaches came into use and in 1823 the first Hackney cabs came to London. It was not until 1830’s, however, that the Handsome Cabs–those single-horse vehicles we know from so many movies–appeared in London.

With a fashionable carriage you might go driving in Hyde Park at five PM, the fashionable hour. You might hire a hack to be seen riding, if you could not afford a carriage. Ladies often drove ponies.

Handling the ribbons was not for the unskilled, or the timid. To drive a single horse is to have around 1600 pounds of muscles in your two hands. You begin to see why men have the advantage in shoulder strength.

It takes a fine hand not to drag on the horse’s mouth and make them hard mouthed, and yet to control the team, and it’s quite an art to drive a horse up in to the bit so that it doesn’t slip behind your control. It’s not at all like driving a car, for a horse is always thinking ahead to how to get its own way about what it wants to do.

To see some great carriage driving, look for three-day event Carriage driving. Drivers have to perform through Dressage phase for movement, a cross-country phase (where you see the grooms clinging for life to the carriage), and an obstacle phase.

Getting Around: Coaches and Stage Travel

Riding in a carriage is also very unlike riding in a car. It’s a good step to climb up into a carriage. And both carriage springs and road constructions were being developed during the Regency–and were not without problems.

Sylas Neville’s diary, dated 1771, recorded a stagecoach journey on the London to Newcastle stage. To travel the 197 miles Stilton to Newcastle took him two days, traveling day and night at a speed of about four MPH. The speed was restricted by the road conditions.

By the 1780’s, private post-chaises could cover the distance from Bath to London in 16 to 18 hours. But the Royal Mail coaches were much slower–until John Palmer put a plan forward for a special coach.

Palmer’s improvements produced a mail coach that left the Rummer Tavern in Bath on August 2, 1784 at four PM, and arrived at the Swan with Two Necks in London, before eight AM the next morning. They traveled 119 miles in less than 16 hours, earning the coaches names such as The Quicksilver.

Up to 1820, most coach horses were changed every 10 – 11 miles. Thereafter, to get better speeds, they opted for even less distances, changing about every six miles.

Average speed could vary between 4 MPH for a slow coach or up to 12 MPH for a fast one. 16 mile an hour tits would be a team of four to six high-strung, well fed horses, and a fast, light private carriage that would only ‘be sprung’ over a short distance.

Problems on the road included mud, ruts, cast shoes, lame horses, broken wheels, dust, collisions, snow drifts, overturns, runaways. On the stage or mail, when going uphill you might even have to get out and walk up the hill to spare the horses.

However, a good road could do well. As Mr. Darcy says in Pride and Prejudice, “fifty miles of good road was ‘little more than half a day’s journey.’ And the roads were so good to Brighton that they were often used for setting speed records.

Now, you might not be able to travel the Brighton road today in a carriage–at least not with as they did in the Regency. But there are other ways to gain valuable experience by going out to take a few riding lessons or even driving lessons–and nothing beats hands-on experience for color in a book.

REFERENCES

The Ultimate Horse Book, Elwyn Hartley Edwards, Dorling Kindersley Horses and Horsemanship Through the Ages, Luigi Gianoli, Crown Publishers

Horse & Carriage; The Pageant of Hyde Park, JNP Watson|

A More Expeditious Conveyance; The Story of the Royal Mail Coaches, Bevan Rider

The Encylopedia of Carriage Driving,Sallie Walrond

The Elegant Carriage, Marilyn Watney

Fox Hunting, Jane Ridley

Hints on Driving, Captain C. Morley Knight

The Young Horsewoman’s Compendium of the Modern Art of Riding, Edward Stanley

Records of the Chase by “Cecil”

Nimrod’s Hunting Reminiscenses