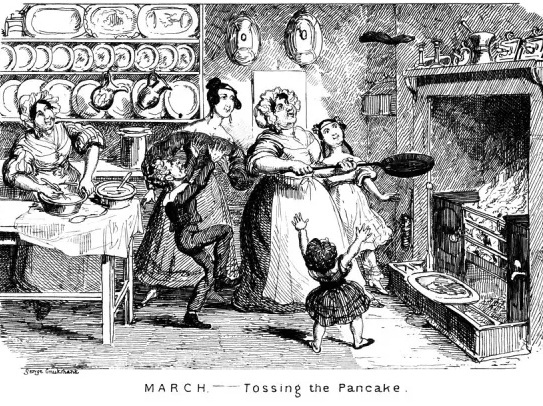

Shrove Tuesday is the last day before Lent begins on Ash Wednesday, typically falling anywhere from February 3 to sometime in early March. Traditionally, Shrove Tuesday Pancakes were made up as a last indulgence with butter and eggs, or all the things that might have to be given up for the forty days of Lent. In 2026, this will fall on February 17.

George Cruickshank’s print in ‘The Comic Almanack for 1837: An Ephemeris in Jest and Earnest Containing All Things Fitting For Such Work’ done under the penname of Rigdum Funnidos shows a cook tossing such a pancake.

English pancakes tend to be more like what Americans think of as crepes and were often served with dinner or tea with just a sprinkle of sugar instead of the US idea of a thick breakfast stack with maple syrup poured over top.

Susannah Carter gives the following recipe in The Frugal Housewife (1822) for pancakes:

“In a quart of milk, beat six or eight eggs, leaving half the whites out; mix it well till your batter is of a fine thickness. You must observe to mix your flour first with a little milk, then add the rest by degrees; put in two spoonfuls of beaten ginger, a glass of brandy, a little salt; stir all together, clean the stew pan well, put in a piece of butter as big as a walnut, then pour in a ladleful of batter, moving the pan round that the batter be all over the pan: shake the pan, and when you think that side is enough, toss it; if you cannot, turn it cleverly; and when both sides are done, lay it in a dish before the fire; and so do the rest. You must take care they are dry; before sent to table, strew a little sugar over them.”

There was no baking powder yet to make fluffy pancakes, and the recipe doesn’t call for any type of yeast. While pearlash was around for leavening (you soak wood ash in water, strain it, then boil it until it makes a moist white powder). This wasn’t much in use in England for it doesn’t show up in cookbooks. Barm, also called ale yeast, does show up occasionally in recipes, but commercial yeast was readily available and used not just in bread, such as in cakes and puddings like “Dutch Pudding or Souster.”

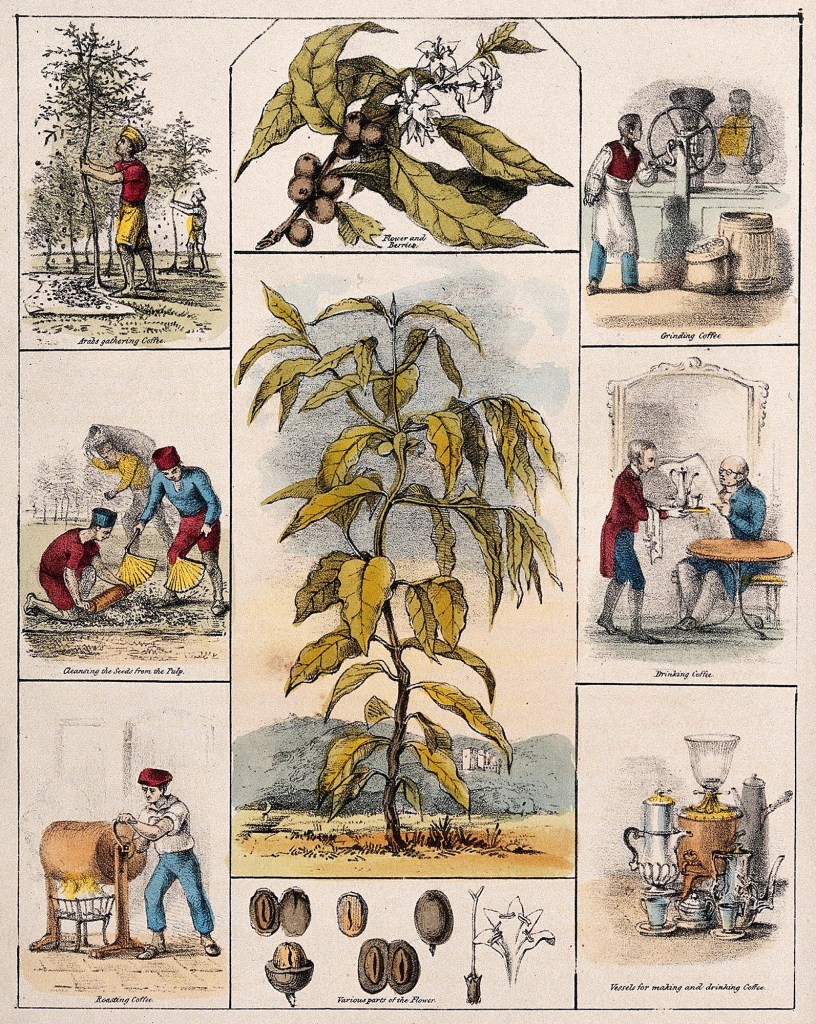

From the garden and farm, John Loudon’s 1822 book An Encylopaedia of Gardening offers up this advise, along with vegetables and fruits, with spellings and punctuation the same as from his book:

FEBRUARY Planning and Preparing, Foaling, Start of Early Lambing in fields, Planting trees and bare root plants such as roses, root crops in, Pare and burn grass lands, Spread manure.

Scotch or Strasburgh cabbage, savoys, borecoles, Brussels’ sprouts, and, if a mild winter, cabbage coleworts, brocolis. Haricots, beans, and soup-peas from the seed-room. Potatoes, Jerusalem artichokes, turnip, carrot, parsnip, red-beet, skirret, scorzonera, and salsify. Spinach, if a mild winter. Onions, leeks, garlick, shallot, and rocambole. Sea-kale from covered beds. Lettuce, endive, celery. American and winter-cress. Parsley, if protected, horse-radish, and dried fennel, dill, chervil, &c. Thyme, sage, rosemary, and lavender, from the open garden; dried marjoram, basil, &c. from the herb-room. Rhubarb-stalks from covered roots, anise, coriander and carraway-seeds, from the seed-room; chamomile, &c. from the herb-room. Red cabbage, samphire. Nettle and thistle tops; towards the end, sorrel leaves, and if a mild winter, sauce-alone. Mushrooms from covered ridges. Sea-belt preserved, and occasionally badder-locks.

Hardy Fruits from the open Garden, Orchard, or Fruit-Room. Apples, pears, quinces, medlars, services from the fruit-room. Some plums from branches hung up in the fruit-room. Dried grapes and currants from branches hung up in the fruit-room. Almonds, walnuts, chestnuts, filberts from the fruit-room. Sloes from dried branches hung up in the fruit-room.

Culinary Productions and Fruits from the forcing Department. Kidney beans. Potatoes. Sea-kale, asparagus. Small salads. Parsley, mint, chervil. Rhubarb. Mushrooms. A pine occasionally; grapes, cucumbers, strawberries. Oranges, lemons, olives, pomegranates. Pishamin-nuts, lee chees. Yams, and Spanish potatoes.

- Borecoles is a type of kale.

- Haricots are green beans.

- Jerusalem artichoke is a hardy, starchy root plant that has nothing to do with artichokes, but has more in common with potatoes and mashes up very well.

- Skirret, also a root plant which means hardy for winter, is said to taste like carrot.

- Scorzonera is another root vegetable that tastes a bit like an artichoke.

- Salsify is also call oyster vegetable since it has a oyster-like taste.

- Rocambole is another name for a shallot, which can still be found in many modern markets.

- Samphire does still show up in English cooking, and grows in marshy areas. It is from the parsley family, looks like baby asparagus, and has a crisp, salty taste.

- Sea-belt and bladder-locks are both types of seaweed.

- Medlars is described as tasting like spiced applesauce.

- Services are a type of strawberry.

- Filberts are what is called a hazelnut in the US.

- Chervril is a herb similar to parsley.

- ‘Pine’ means a pineapple, which are touchy to grow in England (they do look a bit like a pinecone).