Today we have a guest post from author Ella Quinn on tea — so curl up with a cuppa and enjoy!

Today we have a guest post from author Ella Quinn on tea — so curl up with a cuppa and enjoy!

Ah, tea. Once could wax eloquently on the subject of tea, and one has. The small leaves have been the topic of erudite, and sometime heated conversation, especially when talk turns to how tea was drunk over 200 years ago. And why, you ask, would one want to discuss that particular matter? Well… because I am a Regency author, and, therefore, I tend to have conversations with other Regency authors on seemingly innocuous matter.

The actual origins of the drink are said to date back to Sichuan province’s Emperor Shen Nung 2737 BC. In China, tea had the reputation of being helpful in treating everything from tumors to making on happy.

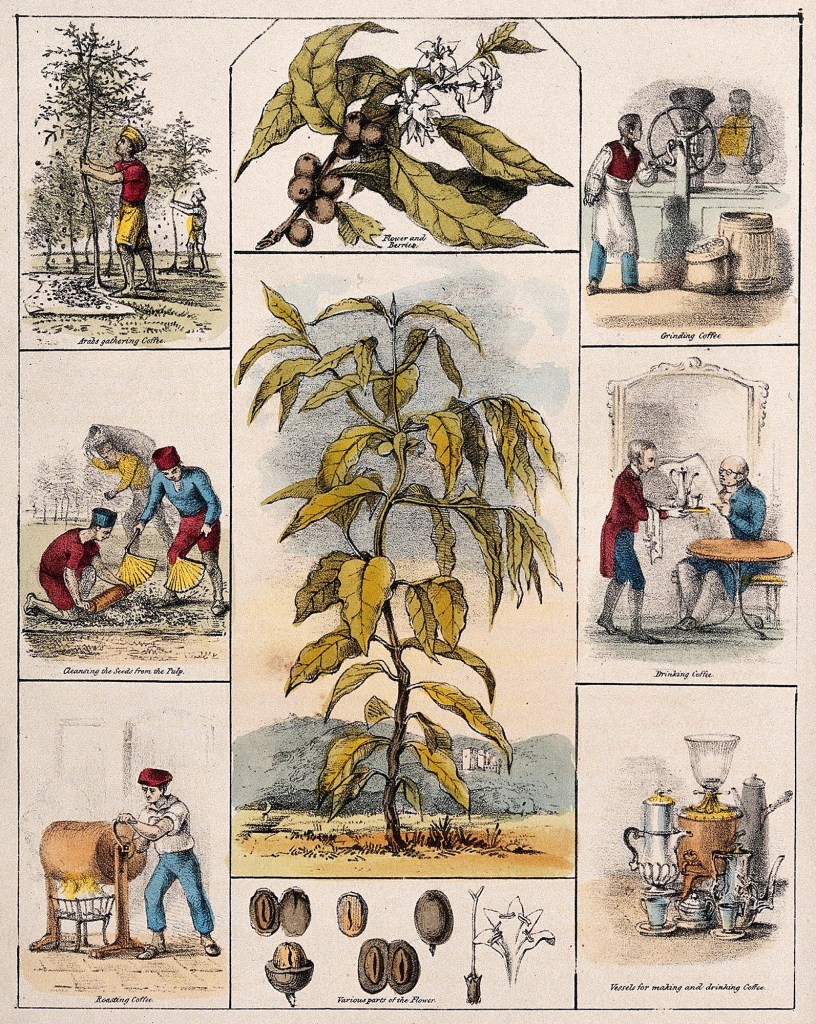

Tea was first brought to England from China in the mid-17th Century. It made its debut around the same time as Turkish coffee and hot chocolate. Tea had been drunk on the Continent prior to its arrival in England as Ladies Arlington and Offory developed a taste for it in Holland and brought some home with them. At the time, tea was hideously expensive, one report in 1666 had it as costing 40s a pound when brandy cost 3. Considering the average lawyer earned the equivalent of £20 per year, it is not surprising that only the wealthy could afford to buy it. It was during this century that tea began appearing in coffee houses as well.

Tea was first brought to England from China in the mid-17th Century. It made its debut around the same time as Turkish coffee and hot chocolate. Tea had been drunk on the Continent prior to its arrival in England as Ladies Arlington and Offory developed a taste for it in Holland and brought some home with them. At the time, tea was hideously expensive, one report in 1666 had it as costing 40s a pound when brandy cost 3. Considering the average lawyer earned the equivalent of £20 per year, it is not surprising that only the wealthy could afford to buy it. It was during this century that tea began appearing in coffee houses as well.

While the men were out drinking coffee, tea and chocolate at coffee houses which were morphing into clubs such as White’s, the ladies followed Queen Catherine’s example (she brought her own tea from Portugal) and remained home to drink tea a chocolate. There appear to be several reasons that coffee did not become popular at home, one was the smell, which many found objectionable.

The earliest painting I found of ladies getting together to drink tea is A Tea Party by Verkolje. Since 17th Century it was customary for the lady or gentleman of the house to actually brew and serve the tea.

The earliest painting I found of ladies getting together to drink tea is A Tea Party by Verkolje. Since 17th Century it was customary for the lady or gentleman of the house to actually brew and serve the tea.

By the late 17th Century, green tea in both leaf and powered form, and black tea called Bohea from the Bohea mountain region were being imported. If tea wasn’t expensive enough, the government decided to tax it, and smugglers opted to take advantage of that decision and a trade smuggled tea began. By the 18th Century the beverage had become so popular that no less than at least fourteen different types of tea were available, as were adulterated teas. Smouch making, the mixing of tea with dried ash tree leaves had begun. Because it was easier to hid smouch in green tea, black tea became more popular. At the end of the century, tea was enjoyed by all social classes.

By the 19th Century, tea was also being imported from India and Ceylon. The beverage was drunk at breakfast, in the afternoon (Jane Austen makes mention of it in1804), evening and in times of distress. A while ago, I ran across a quote from a lady stating that one invited friends to “drink tea” and that the term to “take tea” was vulgar. Unfortunately, I can no longer find the reference.

The popularity of tea also spurred new serving wear, furniture and later in the century rooms in houses were set aside for the purpose of drinking tea.

The popularity of tea also spurred new serving wear, furniture and later in the century rooms in houses were set aside for the purpose of drinking tea.

Now back to the original debate. According to Jane Pettigrew’s A Social History of Tea, which I highly recommend and from whence much of this information has been derived, Tea was drunk with sugar and either sweet milk or cream. It appears that more men preferred cream than did women. Or at least they wrote about it more. When Jane Austen wrote about drinking tea, it was with milk.

Tea plays a large part in my debut novel The Seduction of Lady Phoebe. The hero, Lord Marcus is devoted to tea. Unfortunately, his father will only allow coffee to be served at breakfast. Lady Phoebe, as did most ladies of the time, had her own blend.

Excerpt from The Seduction of Lady Poebe

A low growl from her stomach caught her attention. “I’m famished.”

Marcus nodded. “As am I. When I have a household of my own again, I’ll order breakfast to be served early.”

She turned Lilly toward the gate. “I’ll wager if we go back to St. Eth House now, François, my uncle’s chef, will find something to feed us.”

“Lead on.”

After they entered St. Eth House, Phoebe motioned to Marcus to follow her through the baize door leading to the kitchen.

With a brilliant smile on her face, she approached François, the St. Eth chef de cuisine. “François, we have been riding and are so very hungry. Will you feed us?”

He glanced from her to Marcus. “Oui, milady. Naturellement.”

François gave them each a warm bun with honey before shooing them up the stairs to await their breakfast.

Phoebe took a place at the table and Marcus sat next to her. Ferguson brought tea and she poured them each a cup. The buns were wonderful, tasting of honey and butter. She wondered what François would send up for the rest of their breakfast.

Marcus gave a satisfied sigh. “Phoebe, I can’t thank you enough for the tea. I almost always have to have coffee at home.”

That was very strange. Puzzled, she asked, “Why do you not ask for tea to be served if you don’t like coffee?” It was the first time she’d ever seen him disgruntled.

“I asked for tea once, years ago, and my father gave me coffee. He was so adamant, I never asked again. I still feel like a guest at Dunwood House, as if I’ll be returning to Jamaica. . . .”

THE SEDUCTION OF LADY PHOEBE ~ ON SALE: September, 19, 2013LADY PHOEBE STANHOPE, famous for her quick wits, fast horses, and punishing right hook, is afraid of nothing but falling in love. Fleeing a matchmaking attempt with the only man she despises, Phoebe meets a handsome blue-eyed stranger who sends her senses skittering. By the time Phoebe discovers the seductive stranger is the same arrogant troll she sent packing eight years ago, she is halfway to falling in love with him.

LORD MARCUS FINLEY last saw Phoebe striding regally away, as he lay on the floor with a bruised jaw and a rapidly swelling eye. Recently returned from the West Indies, Marcus is determined to earn Phoebe’s love, preferably before she discovers who he is. Determined to have Phoebe for his own, Marcus begins his campaign to gain her forgiveness and seduce her into marriage.

Can Phoebe learn to trust her own heart and Marcus? Or is she destined to remain alone?

“Lady Phoebe is a heroine Georgette Heyer would adore–plucky, pretty, and well worth the devotion of the dashing Lord Marcus. A marvelous find for Regency romance readers.” — NYT Bestseller Grace Burrowes

“Ella Quinn’s The Seduction of Lady Phoebe is a passionate tale full of humor, romance, and poignancy. Quinn writes classic Regency romance at its best!” — Shana Galen

Preorder or Buy at:

Amazon US

Amazon UK

B&N

Author Ella Quinn has lived all over the United States, the Pacific, Canada, England and Europe before finally discovering the Caribbean. She lives in St. Thomas, Virgin Islands with her wonderful husband, three bossy cats and a loveable great dane. Ella loves when friends connect with her. Visit her at

www.ellaquinnauthor.com, or connect on

Facebook,

Twitter, or at her

blog.