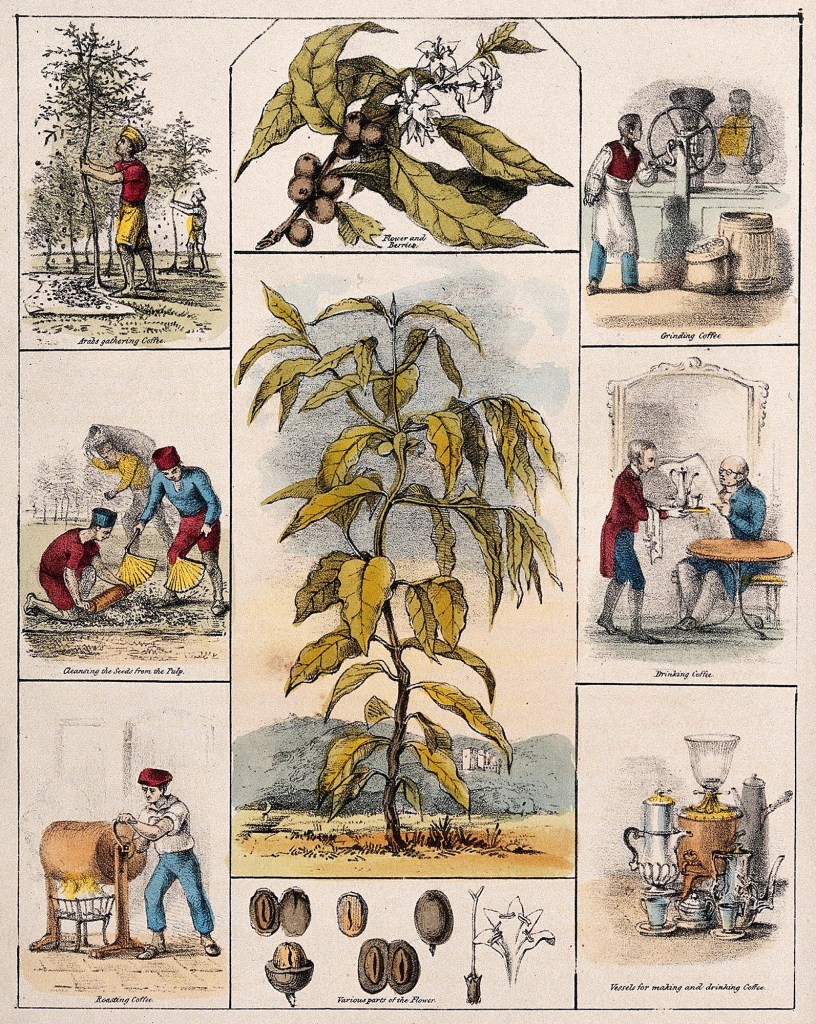

I’ve just finished up the Regency Food and Seasons workshop for Regency Fiction Writers, and there’s always some ephemera that doesn’t quite make it into the workshop. This one is a poster from 1840 showing coffee being grown, what the leaf and bean looked like, roasting, grinding, and serving it up.

We tend to associate tea drinking with England–thanks to the high tea that came along in the late 1800s. But coffee was just as important a beverage–perhaps even more so–in the late 1700s and early 1800s. Coffee houses became all the rage in the 1600s, and continued to be so into the Regency era in England.

Not everyone was a fan of the coffee house (they also would serve drinking chocolate, tea, and punch, and provided newspapers to read). As reported on The Gazette UK website, “On 29 December 1675, a proclamation by the king was published that forbade coffee houses to operate after 10 January 1676 (Gazette issue 1055), because ‘the Idle and Disaffected persons’ who frequent these establishment have led to ‘very evil and dangerous Effects’ and ‘malicious and scandalous reports to the defamation of His Majesties Government’.” Meaning, of course that folks were talking politics. The notice gave warning that, “after the 10th day of January ensuing, to keep any publick Coffeehouse, or to utter or sell .… any Coffee, Chocolet, Sherbett or Tea, or they will answer the contrary at their utmost Perils’. Licences were to be made void, and if continued to trade, given a forfeiture of £5 per month and then ‘the severest Punishments that may by Law be inflicted’.” Naturally, the whole thing went bust, along with a “Women’s Petition Against Coffee” which reported it made men talk too much–it was, of course, yet another political maneuver that lacked popular support.

Folks kept drinking coffee, grocers added the beans to their stock (along with tea leaves), and porcelain manufacture created lovely tea and coffee sets, some as large as 40 pieces including cups, saucers, pots and everything else needed. Silversmiths also did a good trade, such as for this coffee pot, tea pot, creamer and sugar holder from 1800 made by John Emes, with gilt interiors.

Jane Austen wrote in a letter, commenting on her brother’s habits, that, “It is rather impertinent to suggest any household care to a housekeeper, but I just venture to say that the coffee-mill will be wanted every day while Edward is at Steventon, as he always drinks coffee for breakfast.” Coffee would also be brought into the drawing room with tea after dinner, so that guests could have a choice of beverage.

All these thoughts about coffee come–not just due to my being a coffee drinker, for I also love my morning and afternoon tea–but due to a headline that, ‘Your coffee habit could be linked to healthier aging, study finds‘. Good news for those of us who love that morning coffee…and who are getting up in years.

So drink up and enjoy your coffee…and you can still fit in that afternoon tea as well–green tea, after all, is so good for you as well.