One of my favorite quotes about writing comes from Kurt Vonnegut (and if you haven’t read the classic Slaughterhouse Five, I recommend it highly). In Vonnegut’s 8 Rules for Writing, he notes, “Every character should want something, even if it is only a glass of water.” That is a brilliant observation, and this provides natural tension for any scene or the opening of a story.

The actual definition of tension is anything stretched tight. This gives any writer a lot of room. The reader’s curiosity about a character’s background can be stretched out until it becomes tight. A character’s quest for a goal can be stretched very tight with failure after failure. The reader’s interest in how a romance achieves a satisfying ending is yet another way to stretch tension.

All this means is that every character always needs to want something in every scene—this creates automatic tension since the question exists of will that character get it or not, and if so how will the character go about getting that desire.

The other brilliant part of Vonnegut’s rule here is that the want can be simple—it doesn’t have to be world peace or victory over evil, although those are certainly options. Small wants can lead to stories with lots of tension if that want means a lot to the character—or to the reader.

In any romance, the tension is never will they end up together. The tension comes from the HOW—how will this romance end in up a relationship that lasts. In a murder mystery, the tension is HOW will the murder be caught, and this can be wonderfully dark in a mystery where the murderer is also the protagonist. In a horror story the tension is about HOW will the evil be defeated—and it must be defeated, not just avoided, for the world to come back to normal.

All this leads me to the summary that tension needs to start with the first line of the story—that is where the first pull on the reader needs to happen. This means this is a great place for the protagonist to express a desire that is going to lead to the reader asking about how that character is going to get

The desire doesn’t have to be stated as the obvious—it can be implied. The opening line for Slaughterhouse Five is, “All this happened, more or less.” The reader knows there is a narrator who wants to tell a story—and the tension is started with a tug on reality. What is the more, what is the less? That question pulls on the reader, giving us some tension.

It can also be the first paragraph that gives the tug on the reader—that first start of tension in the story. In a novella I write, Border Bride, it starts: “She had been mad to agree to this. Stark, staring mad. So of course it must be love.” The inference is that the viewpoint character wants this madness to be love—she has a desire. The tension is set in the doubt underneath this that perhaps she is wrong, which is why she is doubting the action she is taking. That is the first tug that not all is right in this character’s world.

I think too often writers who are just learning their craft think they have to have big conflict, or big tensions, when it is often the tug, tug, tug of smaller events that better build the tension of the story, taking the reader along step by step into another world.

This is one reason why I love writers such as Elizabeth Daly, a mystery writer who set her books in the 1940s—when she was writing. Check out this wonderful opening line to Unexpected Night, “Pine trunks in a double row started out of the mist as the headlights caught them, opened to receive the car, passed like an endless screen, and vanished.” Wonderfully understated. The want is implicated—the viewpoint character wants to get somewhere. It doesn’t need the obvious stated. It’s also moody, sets the tone for a mystery, and the reader can settle down to enjoy a master story teller at work, caught in the subtle tension of where are we and who is heading into these mists?

Elizabeth George, another master of the craft, opens What Came Before He Shot Her—a why done it—with, “Joel Campbell, eleven years old at the time, began his descent towards murder with a bus ride.” We have tension galore in this line—and we wonder why this boy might want to kill someone. A want, and a tug on the reader. In the opening to The Vine Witch—a luscious novel that should be read and reread—by Luanne G. Smith, we have, “Her eyes rested above the waterline as a moth struggled inside her mouth. She blinked to force the wings past her tongue, and a curious revulsion followed. The strangeness of it filtered through her toad brain until she settled on the opinion that it was best to avoid the wispy yellow-winged ones in the future.” The tug is the, that bit of tension—a toad? Why is she a toad? What happened? She—the toad—might want a meal, but not out of this moth. What will happen next? The promise is here of a world that beckons us inside.

We also have Jane Austen who gives us the much quoted opening from Pride and Prejudice, “It is truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife.” Again, we have a narrator’s voice—an assurance from the first line that we can settle back and trust we will be amused and entertained. But the tension is there. Why is this such a truth—is it really? Who is this man with a good fortune, and what wife does he want? The questions are implied, which is what makes this such a good draw. The reader gets the fun of reading the implications behind the statement.

So this is what the opening of the story should do—it should start to tug on the reader with a want, an implication, a promise of a good read ahead in this story. The tug can be a big one, or a small one, but it must be there. This is the start it says, this is the beginning of the ride—this is not all the stuff that came before, or the background. It offers the tension of want unfulfilled, a need unmet, a curious moment that beckons the reader to step into another world. The background is teased in with other tugs on us—we want to know more because of that tension introduced, and always made greater with more and more tugs. It can be a slender thread that keeps pulling on the reader, but pull we must by offering characters who want things, and questions we raise with a promise of answer coming later if you but keep reading.

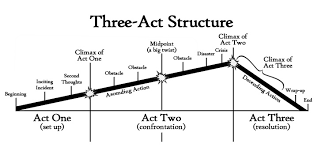

There are as many ways to plot as there are writers. However, one thing I’ve learned over the years is that if you have an idea where you’re going, it can save you from having to do massive revisions. This is not to say you have to know every detail. Sometimes knowing too much can keep you from writing the story–you feel as if it’s already been told.

There are as many ways to plot as there are writers. However, one thing I’ve learned over the years is that if you have an idea where you’re going, it can save you from having to do massive revisions. This is not to say you have to know every detail. Sometimes knowing too much can keep you from writing the story–you feel as if it’s already been told. The idea behind the workshop is that if you plot from trying to think up actions to happen, you’re more than likely going to end up pushing your characters around as if they are paper dolls. The characters are going to come across as one-dimensional and not well motivated to take the actions demanded by the plot (because the plot is being pushed onto them, not pulled from who these characters are). The other problem is the plot is going to seem contrived–the author will have to manipulate the characters to make these actions happen. That’s going to strain the reader’s ability to believe in these characters (and their situations).

The idea behind the workshop is that if you plot from trying to think up actions to happen, you’re more than likely going to end up pushing your characters around as if they are paper dolls. The characters are going to come across as one-dimensional and not well motivated to take the actions demanded by the plot (because the plot is being pushed onto them, not pulled from who these characters are). The other problem is the plot is going to seem contrived–the author will have to manipulate the characters to make these actions happen. That’s going to strain the reader’s ability to believe in these characters (and their situations).