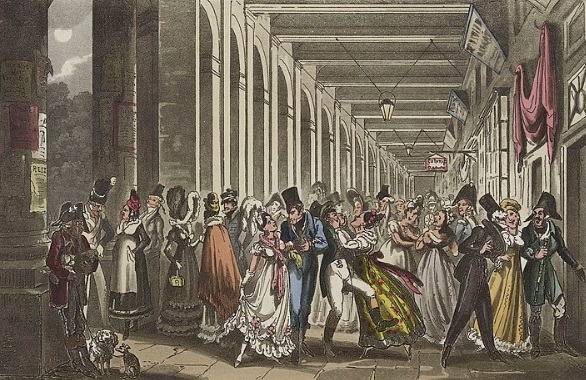

By 1815 the Palais-Royal was already known for being the place to go in Paris not just for a meal, but for gambling, and to indulge in every other vice. John Scott wrote of his visit to the Palais-Royal in 1814: “It is a square enclosure, formed of the buildings of the Orleans Palace; piazzas make a covered walk along three of its sides, and the centre is an open gravelled space, with a few straight lines of slim trees running along its length.”

Scott called it, “…dissolute…wretched, elegant…busy, and idle”

The palace began life in the early 1500s as the Palais Cardinal, home to Cardinal Richelieu, but became a royal palace after the cardinal bequeathed the building to Louis XIII. It eventually came to Henrietta Anne Stuart who married Phillipe de France, duc d’Orléans. That’s when it became known as the House of Orléans.

The building was then opened so the public could view the Orléans art collection, and that began the palace’s more public life. Louis Philippe II inherited the royal palace, and the duc renovated the building, and the center garden was now surrounded by a mall of shops, cafes, salons, refreshment stands and bookstores. The Parisian police had no authority to enter the duc’s private property, which meant it became a hub for illegal activity, and the cafés, particularly the Corazza Café, became a haunt of the revolutionaries. During the French Revolution, the duc dropped his title, changed his name to Philippe Égalité and even voted for the death of his cousin to the end monarchy. That didn’t save his own head. But the Palace-Royal continued on.

Scott writes, “The chairs that are placed out under the trees are to be hired, with a newspaper, for a couple of sous a piece; they are soon occupied; the crowd of sitters and standers gradually increases; the buzz of conversation swells to a noise; the cafés fill; the piazzas become crowded; the place assumes the look of intense and earnest avocation, yet the whirl and the rush are of those who float and drift in the vortex of pleasure, dissipation, and vice.”

On the ground floor shops sold “perfume, musical instruments, toys, eyeglasses, candy, gloves, and dozens of other goods. Artists painted portraits, and small stands offered waffles.” While the more elegant restaurants were open on the arcade level to those with the money to afford good food and wine, the basements offered cafés with cheep drinks, food and entertainment for the masses, such as at the Café des Aveugles.

After the Bourbon restoration in 1814, the new duc d’Orléans took back his title and the Palais-Royal kept its reputation for a fashionable meeting place. It was said, “You can see everything, hear everything, know everyone who wants to be found.”

Scott visited Paris during the peace of 1814 and wrote of the shops, “…they are all devoted to toys, ornaments, or luxuries of some sort. Nothing can be imagined more elegant and striking than their numerous collections of ornamental clock-cases; they are formed of the whitest alabaster, and many of them present very ingenious fanciful devices. One, for instance, that I saw, was a female figure, in the garb and with the air of Pleasure, hiding the hours with a fold of her scanty drapery: one hour alone peeped out, and that indicated the time of the day…. The beauty and variety of the snuff-boxes, and the articles in cut-glass, the ribbons and silks, with their exquisite colours, the art of giving which is not known in England, the profusion and seductiveness of the Magazines des Gourmands are matchless.”

The bookshops sold erotic prints along with French classics, and political pamphlets and the restaurants were crowded every evening and night with anyone who could afford the price of a bottle of wine and a fine dinner. Upstairs were the gambling houses and bagnios, and as Scott wrote, “…the abodes of the guilty, male and female, of every description.” Lanters illuminated the crowds that strolled past along with dancing dogs, strolling musicians, singers, and “….Prostitution dwells in its splendid apartments, parades its walks, starves in its garrets, and lurks in its corners.”

Scott spoke of “The Café Montansier was a theatre during the revolutionary period…” Just such a café/theater went into Lady Lost, as the place where the heroine Simone, also known as Madame de Mystére, practices her illusions.

In March 1815 the Palais-Royal saw more soldiers than it had in ages for Napoleon brought his troops to Paris, chasing out Louis VXIII.

Scott’s book, A visit to Paris in 1814, was published in 1816.

EXCERPT LADY LOST – Jules and Simone dine at the Palais-Royal

Simone stood at the entrance to the Café Lamblin in the Palais-Royal. Even this late, some lingered over their supper. The looking glasses that lined the wall facing the street emphasized the crowd. The other walls, painted white and trimmed with gilt, shone in the light of the Argand lamps set between the silverware and china placed on tables covered with white linen. Ornamental iron stoves warmed the vast space, and four clocks, hung high on the walls, showed the hour as well past eleven. Perhaps three dozen diners remained—gentlemen and ladies, soldiers and courtesans. In Paris, anyone and everyone chose the pleasure of dining out when they had the money to pay the bill. Her mouth watered at the aromas haunting the room—soups and meats, liquors and wines, and the sweet scent of fruit and ices melting into their glasses upon the tables.

To her right, behind a barrier and seated on a rise, the lady proprietor took payment from two men who shrugged into their coats and donned hats. Simone handed her cloak to an attendant and waved for Jules to do the same with his outer garments. A waiter appeared, a long white apron around his waist and flapping at his ankles, partly covering a black vest and breeches. With a bow and a snap of his shoes against the marble floor, he showed them to a table and handed over broad, paper menus.

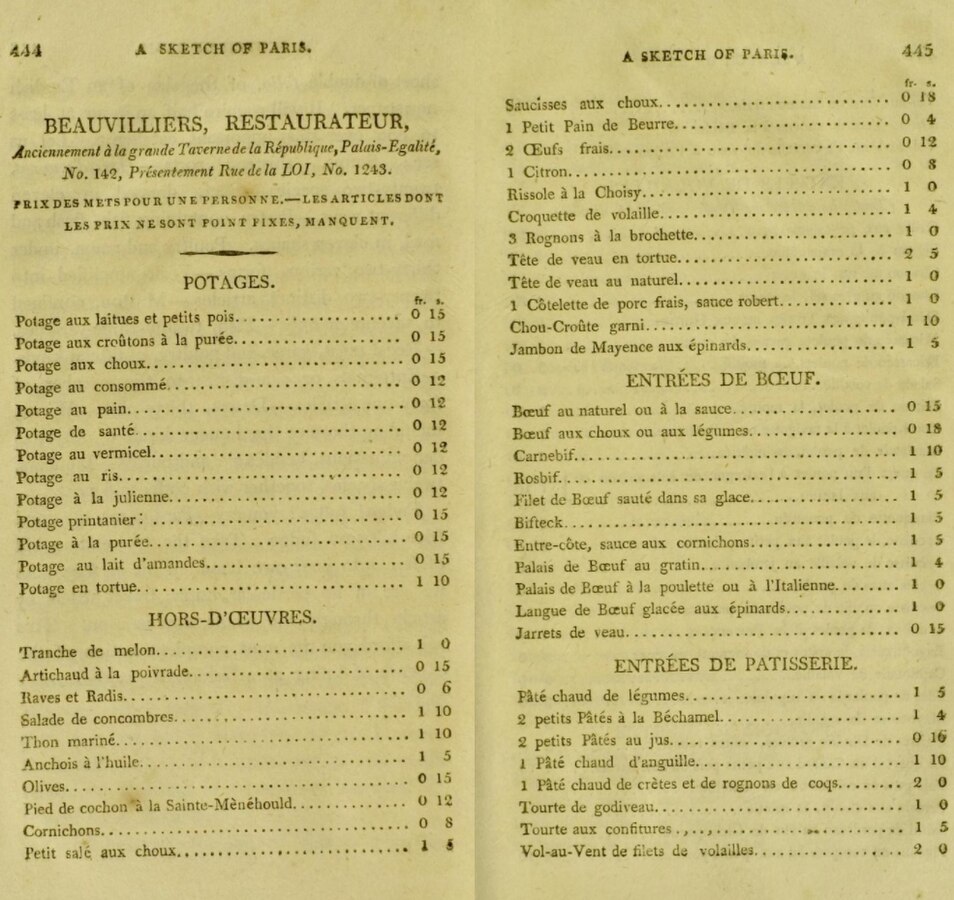

Jules stared at the printed sheet. “Not as extensive as that of Le Beauvilliers but far better prices.”

Simone glanced around the room. The wine and liquors flowing endlessly—along with coffees—and waiters dodged tables with trays of food and drink. Laughter and conversation rolled across the room. No one in Paris liked to refuse the flow of francs into the hand, not even for so late a meal.

She glanced back at Jules. “Prices? Do not be so provincial as to think that is all that matters.”

Putting aside his menu, mouth twisted up on one side, he shook his head. Blue eyes gleamed bright. “Oh, but I am just that. A wine merchant who has never before been to Paris, I am amazed by such an extensive printed menu. Order what you wish. I think we can stand the nonsense.”

“You may regret that,” Simone told him.

She ordered lobster soup from a choice of half a dozen others, cold marinated crayfish, chicken fricassee with truffles in a sauce of leeks and oysters, duck with turnips from an array of roast birds, a side dish of asparagus and one of early peas, a dessert of cheese and nuts, and a bottle of Volney, which Jules sipped and sent away, ordering a Latour instead, which indeed tasted better but would take more coins from his purse.

Dishes came and went. Jules kept up an astonishing chatter about Paris, the food, droll comments on the other diners, and everything but what lay between them.

She pushed at the peas on her plate with her knife and glanced at Jules. “You manage to say a great deal without saying much of anything.”

He held still as only he could, studying her, eyes a sharp blue in the glow of the Argand lamps. “The art of polite discourse. It is second nature. Would you care for more of the duck? I must say, they have a pleasant way with it. The skin is crisp and the taste a delight. They must feed them good corn before they come to the kitchens. Then you may tell me if you think Henri had any part in poor M’sieur Breton’s demise.”

Putting down her knife, she propped one elbow on the table and cupped her cheek with one hand. “That is…no, tell me first, what transpired with those men who took you up? Why do you not speak about that?”

He pushed at a slice of duck with his fork. “Will you in turn tell me if your brother would have jumped for the chance to meet up with the not-so-good duc in my place?”

Straightening, she smoothed the napkin on her lap. “Do we talk of such things here? Where others might listen?” A woman’s laugh pulled her attention to a table with four soldiers and two ladies whose dress—or lack of such a thing—proclaimed their status as those who sold their favors.

Jules waved his wine glass at the room. “Everyone else is bent on pleasure of one sort or another. We might be the only sober souls in this fine establishment.”

She traced a fingernail along the edge of the tablecloth. “Henri…he would not…no, M’sieur Breton was his friend. A good friend.”

“Had he known the man long?”

“No, but that is Henri. He charms everyone quickly. We only met the m’sieur after we come to Paris. Now do I get a question?”

“It has gone beyond coincidence that your brother is a friend—or perhaps I should say was—friend to the late M’sieur Breton. Now we have the duc embroiled in events—the Butcher of Lyons you named him—and it all has me wondering if your parents might have lived in that charming city. Perhaps during the Revolution? That automaton reveals also that your father was a man who made expensive clockworks for those with money.”

With a small shrug, she took up her wine. “What would you have me say?”

“You may act as casual as you wish—you are practiced at that with your stagecraft—but I will have the story. Consider it a fair exchange for dinner.”

“What of payment in an answer for an answer? I am curious, too, and have questions. Why are you not in London? Do you have no wife, for you keep only the mistresses?”

“Multiples is it? You think perhaps I have one woman for each day of the week, or perhaps only one for each season of the year? They are expensive things, and I have no wish to beggar my estate for any such entanglements.”

“Then you have casual liaisons? Was that true of the woman you once wanted to marry as if…for one that, you sound as if you don’t want to speak of her at all?”

“My past has no bearing on the incidents of tonight. It is yours that stirs my interest. May I serve you more of the chicken? You may then tell me of this tie between yourself and Lyons, for you speak of the past as if it is far too present, and the excesses of Madam Guillotine’s rampage certainly reached everywhere in France. Come now—a straight question and a straight answer. Did the Butcher of Lyons touch your family?”

“The past can haunt us all—can it not? What is it you really do in London? Do not the ladies interest you?”

“Ah, now you make me into a gentleman who spends all this time only with other gentlemen. I’ve had other things to occupy me—the world has been sorely troubled of late, and ladies…courting takes a great deal of work. There are rides and walks and dancing to be done. Flowers sent, and if you get that wrong they either wilt too quickly or any real interest does the same. Turn your back but once, and the lady is off on some other man’s arm. Now, what of you? I expose myself, but you remain the lady of mystery? Since you ask it of me, I shall be forward as well and ask why you are unmarried?”

Holding up her hand, she ticked a count on her fingers. “I do not plan to marry a soldier, and look around just now—that means most men in France. Second…actors. I meet many and I follow Maman’s advice and leave them to flirts only for it never ends well.”

“That does not surprise overmuch.”

“Third…” She wiggled her fingers and picked up her fork again. “Third is that I do not want to keep a shop, or run a tavern, and even that sort thinks a woman who goes onto a stage is not respectable, but I am!”

He reached for one of the plates to serve himself more asparagus that had come out with an excellent white sauce that did tempt her, but she would not allow him to divert her focus. She put her hands in her lap.

Glancing at her, he put down the asparagus. “If you will not finish this, I shall. Will you have more of anything else?”

She plucked a green spear from the plate and waved it at him. “Answers. Why are you not in the army? Is not every man fighting on one side or another? Why are you really here? We are back to you talking around and about. Do you think I do not know distractions? That is the principle of sleight of hand.” She bit into the asparagus, then licked her fingers. When she held up her hand again, a coin glinted in her finger tips. With a quick move of the other hand, the coin vanished, and she showed him bare palms.

Putting down his fork and knife, he fixed his stare on her. Heat bled into her face, but she met that direct gaze of his. For a moment, he pressed his mouth tight and hesitated as if making up his mind about something.

Finally, he threw his napkin onto the table. “Very well, if you must know, you must. As to a uniform, it was considered, at least by me, but responsibilities kept me from doing more than that, along with…well, at the time—and this was a long time ago—the woman I wished to court had vapors at even a mention of something so vulgar as fighting and armies. Odd, really, considering she eventually deserted her husband to run off with a sailor. Actually, a captain at the time, although not in the British Navy. However, I also have wretched aim, and while I look very good on a horse, I am not given to charging about. I prefer to think things through and take my time, and that is a quality I found I could put to use elsewhere.”

“Bah—you still tell me nothing. What do you mean, ran off? She is alive still? And she was married when you wanted to court her, or she did marry elsewhere after the courting?”

“We slip from the more pressing topic at hand—that of your brother’s involvement in a death.”

She stiffened. “Do you tell me…did you…? This woman, she is—is no more?”

“Please do not speculate. Far too much of that has dogged me over the years. What I will say is that seventeen is a very stupid age, one I am grateful to have outgrown. Also, her husband suffered more than I at that time. But the situation as well as my family history stirred up old talk about my family, for scandal dogs us like hounds on a high scent, even when I should rather leave all of it far behind.”