Cooking is one of my favorite pastimes—eating and learning about good food is a pleasure. This means it was not difficult to dive into the research needed for a restaurant in Paris of 1815 for the setting of Lady Lost (which comes out in March).

France gets the credit for inventing the more modern idea of a restaurants, and they certainly came up with the name. The word comes about in 1806 for “an eating-house, establishment where meals may be bought and eaten,” but comes from a “food that restores” from the Old Frence restorer.

The original idea was to serve up a healthful bouillon—basically a bone broth or consommé as a restorative. This was also to get around the strict guilds that made selling bread, meat, fruit, and vegetables separate affairs. In 1765, a gentelman named A. Boulanger opened a restaurant on what was then rue des Poulies (now rue du Louvre). It was his idea to serve a wide rage of food—and Boulanger offered up menus, waiters, and small, round marble-top tables. A new business was born.

The term “Gastronomie” comes about in 1801, in a French poem by Joseph Berchoux, and was translated into English in 1810 as: “Gastronomy or a Bon-vivant’s Guide: A Poem”.

The phrase établissement de restaurateur was shortened, and there were soon enough restaurants that the guide L’Almanach des Gourmands was published annually from 1803 to 1812 by Grimod de La Reynière.

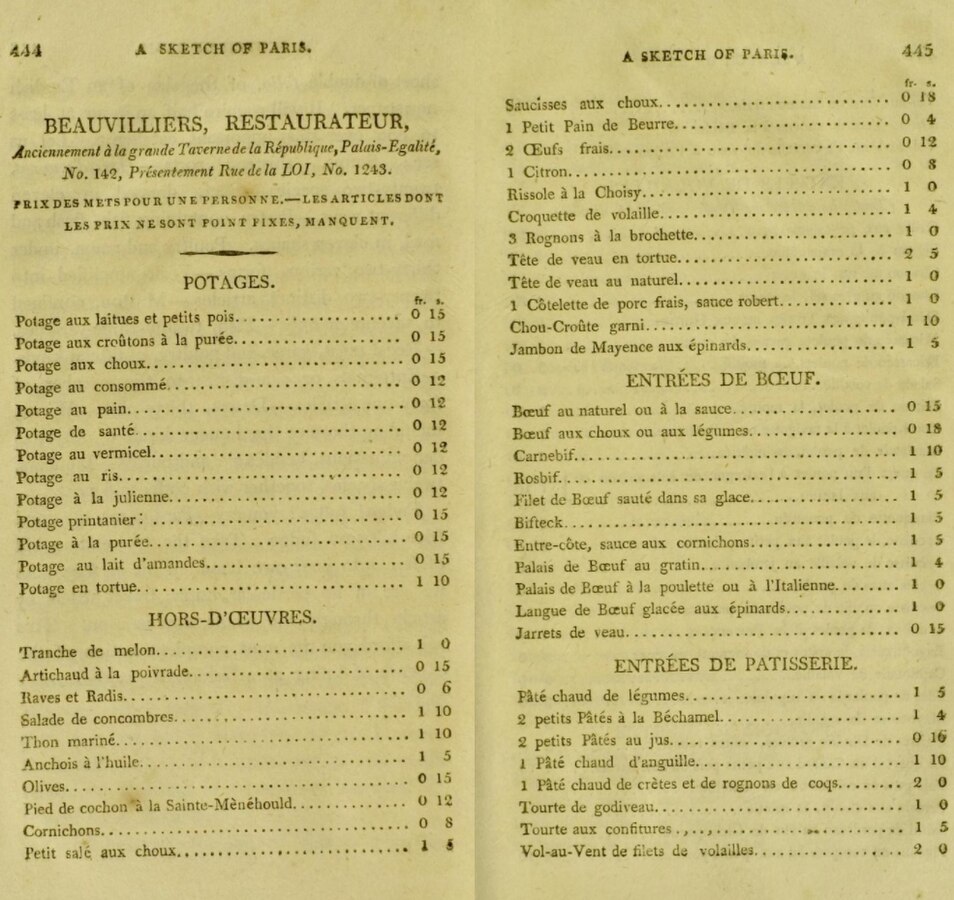

In 1782, Antoine Beauvillier opened Grande Taverne de Londres on rue de Richelieu, and went on to write L’Art du Cuisinie, published in 1814. He had to close that restaurant when things got a bit too hot in Paris during the Revolution, but he then opened Beauvillier’s. Jean-Anthelme Brillat-Savarin said, it was “the first to combine the four essentials of an elegant room, smart waiters, a choice cellar, and superior cooking.”

Francis Blagdon, Englishman, wrote of Beauvillier’s in 1803, “The bill of fare is a printed sheet of double folio, of the size of an English newspaper. It will require half an hour at least to con over this important catalogue. Let us see; Soups, thirteen sorts. — Hors-d’oeuvres, twenty-two species. — Beef, dressed in eleven different ways. — Pastry, containing fish, flesh and fowl, in eleven shapes. Poultry and game, under thirty-two various forms. — Veal, amplified into twenty-two distinct articles. — Mutton, confined to seventeen only. — Fish, twenty-three varieties. — Roast meat, game, and poultry, of fifteen kinds. — Entremets, or side-dishes, to the number of forty-one articles. — Desert, thirty-nine. — Wines, including those of the liqueur kind, of fifty-two denominations, besides ale and porter. — Liqueurs, twelve species, together with coffee and ices.” Below is just part of the menu sheets showing prices.

London continued on with taverns, coffee houses, chop houses, confectioners that served tea, sweets, ices and pastries, and a few gentlemen’s clubs. The Epicure’s Almanack by Ralph Rylance came out in 1815, listing more than 650 eating houses, inns and taverns in London, but was a financial failure. The English just were not that interested.

By 1815, the Palais Royal alone had fifteen restaurants, twenty cafes, and eighteen gambling halls—not to mention the brothels. This included Café de Chartres. Other restaurants included Le Grand Véfour next door to the Palais Royal gardens, Le Procope in Saint-Germain-des-Pré and said to be Bonaparte’s favorite restaurant, Véry which moved to the Palais Royal in 1808, Frères Provençaux in the Palais Royal, and the Café des Aveugles was one of those in the basement of the Paris Royal that offered cheaper prices. In 1815, the Café Anglais opened on the corner of rue Gramont and the Boulevard des Italien, and that boulevard would become extremely popular over the next few decades for restaurants and cafes.

There’s the saying about many sauces in France and one religion, but the opposite in England, and often attributed to Voltaire, but which comes from Louis Eustache Ude’s 1829 book, The French Cook; A System of Fashionable and Economical Cookery, Adapted to the use of English Families. The quote is, “It is very remarkable, that in France, where there is but one religion, the sauces are infinitely varied, whilst in England, where the different sects are innumerable, there is, we may say, but one single sauce.” He was speaking of the English penchant for a white sauce of butter, with a little flour and then perhaps some anchovies or capers, put over most everything.

Back to Paris of 1815—and there were at least a couple hundred of restaurants, some out to attract the wealthy but others serving up food for the average man and woman. The café’s had figured out the idea of putting tables outside to attract customers to sit with a coffee. The Parisians drank lots of coffee, offered along with the inevitable wine, and sometimes chess as well. Pastries, of course, came out along with cakes and bread and cheese. Soups were always a popular meal—despite what the song says about ‘April in Paris’ springtime is lots of wet and March of 1815 served up more than a little bad weather.

A meal might be had for a few sous, or the francs piled on with an array of dishes served up—the wine was generally the most expensive item on any menu.

All of this kept making me remember a trip to Paris—the street food was amazing, as was almost any café serving up crepes or fondue (interestingly Homer’s Iliad describes a mixture of goat cheese, flour, and wine that is basically fondue, but the Swiss came up with their version to use up leftover bread and cheese—a cheap and easy meal.) It is said that the version with meat was created in the Middle Ages in the Burgundy region of France, and the word fondre means to melt in French. Like most foods, everyone seems to have come up with their version. And…oh, the patisseries!

Which are nothing new to Paris, as shown in the print below, entitled, “The English Revenge or, The Patisserie at the Palais Royal” by John Sharp, from 1815, no doubt after Waterloo, with the English eating up all the sweets in the shop. The poor shop girl doesn’t look happy about it, even if she is selling out of everything. Which seems a very Parisian attitude.

All of this made for a fun bit of research for the book when I had to weave in a meal, or put a conversation into a café, which were all considered suitable places for women as well as men, and isn’t it nice to know the cafés and restaurants of Paris still seek to serve up some of the best food that can be had.